Breeding Bird Atlases (BBA)

Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

Chimney Swift

Chaetura pelagica

Egg Dates

May 31 to late July

Number of Broods

one; may re-lay if first attempt fails.

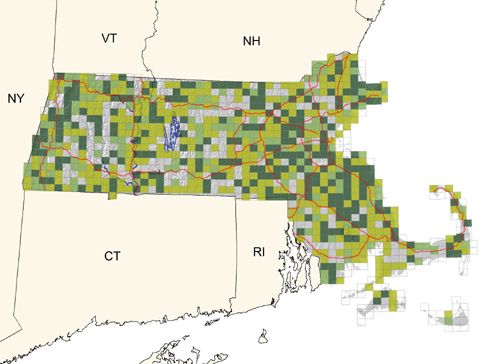

As likely as not, the spring arrival of Chimney Swifts will be announced by a rapid series of loud, harsh chips falling from the sky in late April. A glance skyward will reveal dark, cigar-shaped birds soaring or dashing about on long, sickle-shaped wings. Prior to the arrival of European settlers, Chimney Swifts nested in hollow trees. The number of nests in a given tree was dependent on the size of the cavity. Since then, swifts have adapted to the advances of humankind and in Massachusetts are now reported to nest exclusively in chimneys, although, in other regions, barns, silos, or even the traditional hollow trees may occasionally be used. Swifts are widely distributed in Massachusetts. They are most abundant in river valleys, where smokestacks of abandoned mills provide ample nesting and roosting space, and are decidedly less common on Cape Cod and the Islands than elsewhere in the Commonwealth. During migration, especially in fall, large flocks composed of a hundred or more birds are seen frequently.

More than any other species, the Chimney Swift is an aerial specialist, feeding solely on insects obtained while on the wing. Since swifts are strictly insect eaters, they are best seen in the morning and late in the evening when they course low to the ground. At midday, they are apt to be beyond vision in quest of insects that have ridden warm air currents to great heights. There are also reports of swifts foraging at night. The feet of swifts are poorly developed and serve only to help them cling to vertical surfaces. Most observers will never see one at rest during an entire career of watching. The calls are a series of chip or chit notes, often run together to produce a shrill chatter.

Occasionally, the first Chimney Swifts appear as early as mid-April, and spring migration continues through mid-May. Breeding normally commences in late May or early June. The only visible sign of nesting activity is called twigging, whereby birds will snap the ends of dead twigs off trees. At the onset of breeding, Chimney Swifts are often seen flying in trios, apparently two males vying for a mate. Copulation, like most activities of swifts, is probably accomplished during flight (Sutton 1928).

The nest is shaped like a half-saucer, constructed solely of twigs and attached to the surface of a chimney with a glutinous saliva. Nests may be located near the top of a chimney or 20 feet or more below the opening. Although firmly attached, they may be washed loose during heavy rainstorms. The normal clutch is four or five (range three to six) white eggs. One Massachusetts nest in the Millbury area contained three eggs on May 31 (DKW), and another in Wendell held four eggs on July 2 (CNR). Both sexes share in incubation, which lasts an average of 20 days. Hatching at the Wendell nest began on July 11 (CNR). As the young mature, they leave the nest and cling to the vertical sides of the chimney. They first fly at 28 to 30 days of age. Various observers in Massachusetts report adults entering and departing chimneys frequently during the day, presumably to feed young, from late June through early August, and sometimes to the end of the latter month. The late date for unfledged young is August 28 in Pelham (Nice 1933). One brood is raised each season, but, if weather conditions or human activities cause a nest failure, the swifts will generally make a renesting attempt, and these undoubtedly account for the late breeding dates. A long period of cold, wet weather can make insects difficult to capture and have fatal results for both old and young swifts.

Autumn migration occurs principally in late August and early September but may continue to mid-October. Numbers of migrants are much greater in fall, and observing several hundred swifts first circling and then entering a roost at dusk can be very engaging. The exercise lasts about half an hour, and during peak activity some 40 percent of all the birds that will roost will do so within three minutes, swirling spectacularly into the chimney as though caught in a whirlpool. Most of our swifts have departed by mid-September for wintering grounds in the upper Amazon basin of South America.

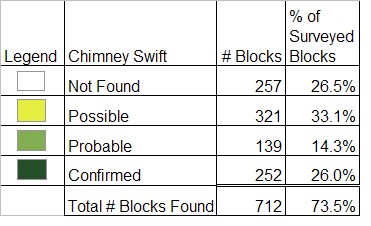

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: common and widespread; less common on the Cape and Islands

Leif J. Robinson and Eliot Taylor