Breeding Bird Atlases (BBA)

Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

Great Horned Owl

Bubo virginianus

Egg Dates

February 15 to May 15

Number of Broods

one; may re-lay if first attempt fails.

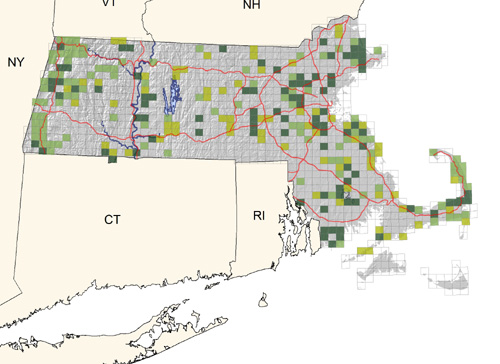

The extensive range of the Great Horned Owl includes nearly all of North America. It is a common species throughout Massachusetts but is absent from Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket. This owl is definitely much more widespread, especially in Worcester County and surrounding regions, than the Atlas map indicates.

The Great Horned Owl occupies a variety of habitats. It inhabits dense forests, which may be coniferous, deciduous, or mixed, as well as smaller woodlots; and it especially favors woodlands adjacent to marshes, swamps, farmlands, rivers, and ponds. This versatile bird adapts well to the presence of humans, as evidenced by the high number of breeding confirmations from densely settled areas of eastern Massachusetts. For roosting purposes, it has a definite preference for dense stands of evergreens of any kind, which offer good camouflage when an owl sits erect close to the trunk of a tree.

Great Horned Owls become most vocal during late December through January and up to the beginning of nesting in February. Vocalizations are almost as varied as those of the Barred Owl and range from deep booming hoots to whistles, shrieks, screams, and hisses. The resonant hooting call can be heard for a distance of several miles on a still night and is generally composed of five notes that sound like whooo-whooo-whoooooo-whoo-whooo.

The distribution of the Great Horned Owl coincides with that of the Red-tailed Hawk, and the owl’s nest is often one that has been abandoned by the latter. Many of these nests are used several years in succession, with the hawks and the owls alternating from one nest to another every year or two. In Massachusetts, Great Horned Owls sometimes also use the old nest of another species of hawk or an Osprey, or that of a crow, Great Blue Heron, or squirrel. Hollow tree cavities or crotches where debris has collected are also utilized. The birds have readily accepted open artificial nests constructed for them. Locations of 21 Massachusetts nests were as follows: 13 in White Pine at 40 to 70 feet, 5 in Pitch Pine at 38 to 65 feet, 2 in oak at 25 and 30 feet, and 1 in American Beech at 31 feet (ACB, CNR).

The Great Horned Owl is the earliest nester of our native birds, usually laying its eggs between February 20 and March 25. The clutch almost always consists of two eggs, but the range can be from one to three, and sometimes four. One brood is raised each season, and on rare occasions a second clutch is produced if the first is lost. Incubation usually begins with the first egg and is performed by the female for 28 to 30 days. She will remain on the nest even during severe weather conditions and may be found covered with snow.

The young are brooded nearly continuously for the first two weeks. At three weeks of age they are about half-grown, and the primary feathers are developing. By the sixth week, they are quite active and begin testing their wings and hopping about the nest and nearby limbs. The young first take to wing during the ninth or tenth week but still depend on the parents for most of their food over the next three weeks. In Massachusetts, nestlings have been observed from March 25 to May 21, and the earliest fledging date was April 26. The latest young are usually out of the nest by the end of May (CNR, BOEM, TC). Brood sizes for 114 state nests were one young (48 nests), two young (56 nests), three young (10 nests) (CNR, BOEM, TC).

The diet of the Great Horned Owl is the most varied of all our birds of prey. The long list includes many species of insects and other invertebrates, reptiles, amphibians, fish, birds (from sparrows to geese and including other species of owls and hawks), and mammals (from rats and mice to skunks, foxes, and cats). All undigestible material such as bones, teeth, claws, feathers, and fur are formed into pellets, which are regurgitated on a regular basis. An owl’s diet is revealed by the contents of its pellets.

The juveniles remain in the territory throughout the summer, following the adults, learning to hunt, and making demands for food that are met increasingly less often. When fall arrives, the young have acquired adult plumage and are proficient fliers and hunters, although some may continue to beg for food during October. Autumn is the time for separation, and the young are either forced out by the adults or drift away voluntarily to seek out territories of their own. These are usually within a 30-mile radius from where they were reared.

This species is essentially nonmigratory, except during especially severe winters when prey becomes extremely scarce or when immature birds seek out unoccupied territories and occasionally move long distances. One such owl banded in Billerica was recovered two years later in Bingham, Maine, a distance of almost 200 miles.

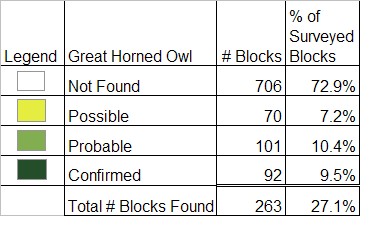

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: widespread but uncommon; most common in southern coastal regions but absent on the Islands

Michael Olmstead