Breeding Bird Atlases (BBA)

Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

Eastern Screech-Owl

Otus asio

Egg Dates

March 7 to May 15

Number of Broods

one; may re-lay if first attempt fails.

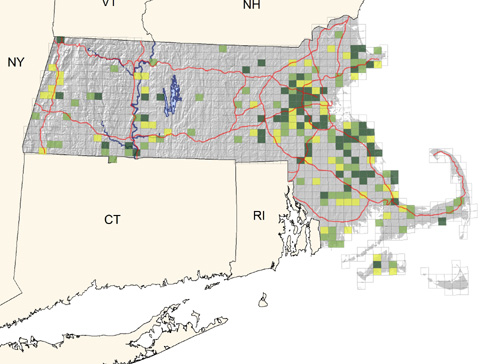

The Screech-Owl occupies an extensive range in North America east of the Rocky Mountains from southern Canada south to the Gulf Coast and Mexico. It inhabits a variety of habitats, preferring open deciduous forests, small woodlots, parklands, orchards, and even residential areas. In Massachusetts, it is most common and widespread in the lowland, hardwood forests of eastern Massachusetts and the Connecticut River valley. It is decidedly less common or even lacking in the higher elevations of Berkshire and Worcester counties, where coniferous growth begins to predominate, and on outer Cape Cod and Nantucket, where the lack of trees of adequate size is the limiting factor.

Heard throughout the year, screech-owls become most vocal from late winter to early spring, prior to and at the commencement of the breeding season. Typical vocalizations during the nesting period (determined by the response given to imitations of the calls) are low monotone wails, or trills, repeated regularly every few seconds for several minutes’ duration. A few whinnies (trills that abruptly rise and slowly descend in pitch) are interspersed among the repeated monotones. Usually, only one member of a pair answers, almost certainly the male. The vocalizations seem to change with the seasons. In winter, responding owls usually produce a long series of descending whinnies, given every few seconds, with only a few of the trills mixed in. A series may last for several minutes and include many repetitions.

Eastern Screech-Owls do not construct a nest. Instead, they select a natural tree cavity, a hole drilled by a woodpecker, or nest box in which to lay their eggs. Nest sites are often near a brook or pond, and the birds will use Wood Duck boxes (Olmstead). Seven Massachusetts nests were located as follows: three natural cavities in apple trees in orchards, three old flicker holes in dead pines or poplar, and one natural cavity in an oak (ACB). Heights ranged from 5 to 35 feet.

The clutch size is usually four or five (range one to eight). In Massachusetts, the peak egg-laying period extends from late March through mid-April. The eggs are laid at 2- or 3-day intervals, and incubation does not always begin with the first egg. Incubation, by the female, has been reported as 21 to 30 days (average 26 days), and the male may roost near her in the cavity. He feeds her during this time and, once the young have hatched, supplies both his brooding mate and the owlets with food for two weeks. Food items include small mammals, insects, earthworms, reptiles, amphibians, fish, and small birds. The young leave the nest and fly in four to five weeks. Brood sizes in 19 Massachusetts nests were two young (6 nests), three young (5 nests), four young (4 nests), and five young (4 nests) (Olmstead). Families may remain in close association at least through the end of summer.

Eastern Screech-Owls occur in two main color morphs, red and gray. An individual’s color is independent of age, sex, or season, and broods may contain young of both types. In northern portions of the range, the gray birds apparently predominate. It has been suggested that the red-morph owls have higher energy demands and are less likely to survive during severe weather conditions.

Seasonal movements of screech-owls are minimal. The species generally is believed to be nonmigratory, except perhaps in the most northerly parts of the range. The size of an owl’s territory may be quite large, with the bird occupying various portions at certain times of the year, thereby creating the illusion of migration. Postbreeding dispersal of young birds can contribute to the illusion, and it may account for some long-distance movements. Although screech-owls have been known to wander to the Canadian Maritime Provinces and some banding recoveries have shown movement of at least 200 miles, most evidence supports the nonmigratory theory.

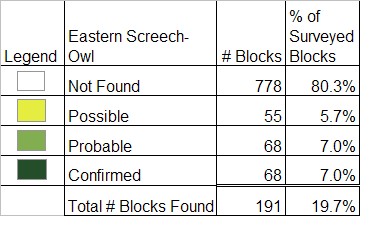

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: common in eastern deciduous woodlands; less common or lacking at higher elevations and along the southeastern coastal plain

Oliver Komar