Breeding Bird Atlases (BBA)

Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

Black-billed Cuckoo

Coccyzus erythropthalmus

Egg Dates

May 16 to July 5

Number of Broods

one

In the mixed, mainly deciduous woodlands that cover the greater part of Massachusetts, the Black-billed Cuckoo is a fairly common summer resident. Among the oak, maple, and birch, it lives the life of a hermit, moving furtively among the branches, seldom venturing into the open for more than a few moments. Owing to its retiring nature, the Black-billed Cuckoo is among the least well known of our breeding species; to many it is no more than a voice in the woods.

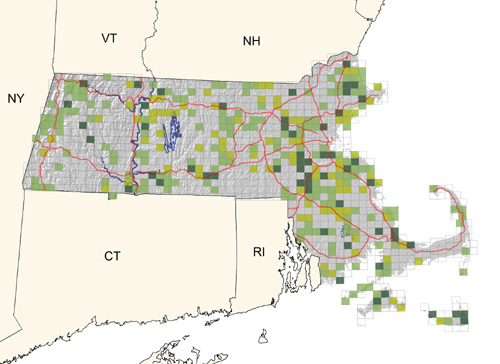

During the Atlas period, the species was confirmed throughout the state. Many observers have noted that in the years following the Atlas, it has become scarce or absent from many areas formerly frequented. Whether this is part of a cycle or a long-term trend remains to be seen. Like its close relative, the Yellow-billed Cuckoo, it often frequents shrubby tangles and wet thickets, but the Black-billed Cuckoo also inhabits tracts of mature forest.

While occasional individuals arrive in late April, most of the spring migration occurs in May. Sometime during the second week of the month, as the hardwood forest is just attaining full foliage, one may first expect to hear the calls of the Black-billed Cuckoo. From its perch, hidden within the blossoming canopy, the cuckoo issues forth a long series of woody notes, in groups of two to four coos, phrase following phrase: coo-coo-coo, coo-coo-coo, coo-coo-coo, coo-coo-coo, coo-coo, coo-coo-coo. A long series of single coo notes, preceded by a harsher introductory note, also identifies this species. There are a variety of other calls, including some harsh kuk notes, some of which are difficult to distinguish from those of the Yellow-billed Cuckoo.

In parts of their range of the South and West, cuckoos are commonly known as Rain Crows because they are believed to sing more frequently during cloudy periods. In truth, the Black-billed Cuckoo may be heard at almost any hour of the day or night. Well before sunrise on a warm May morning, its calls, with those of the thrushes, initiate the dawn chorus. In the breeding season, there are even observations of this species calling in flight at night.

The elusive cuckoo generally builds its nest at the edge of the woodland, well concealed among the dense cover of a young evergreen or thick shrub. Most nests are placed within 2 to 4 feet of the ground, rarely as high as 6 to 10 feet. Massachusetts nests have been recorded in apple, Red Cedar, barberry, Chinquapin Oak, and honeysuckle (ACB, CNR). Nests are typically rather flimsy affairs, loosely constructed of twigs and lined haphazardly with leaves. There are records of well-made nests, including two from Massachusetts, built more substantially and well lined with leaves and catkins (ACB).

The clutch size of the Black-billed Cuckoo is variable. In an undisturbed nest, two or three eggs may be the rule. Yet, both Black-billed and Yellow-billed cuckoos share a tendency toward brood parasitism, a characteristic of their old-world relatives; and females occasionally drop an egg into any convenient nest, though most often into that of another cuckoo. Nests containing up to eight eggs have been discovered, almost certainly the work of two or more birds. The clutch sizes for 9 Massachusetts nests were two eggs (2 nests), three eggs (5 nests), four eggs (2 nests) (DKW, CNR, Meservey). Massachusetts egg dates have been recorded from mid-May to early July, but in other New England states eggs have been found through the end of August. It is very probable that the situation in Massachusetts is similar, and the recorded egg dates do not represent the full range. Reports of fledged young indicate that eggs are found at least through early August. There is no evidence that more than one brood is raised each season nor that the species renests, although the protracted laying season suggests that this probably does occur.

Whatever shortcomings in nest building and egg depositing they exhibit, Black-billed Cuckoos are nonetheless very attentive parents. Both the male and female share the two-week incubation duties. Young are fed by regurgitation, adults transferring food deep into a nestling’s throat through a laborious pumping action. During their first week of life, young cuckoos develop into incredible looking creatures. Their black skin is covered with a fabulous array of bristly quills, which, while in place, create a bizarre porcupine effect. Quite suddenly, at 6 or 7 days of age, the contour feathers break out of the tubes and the young begin to look like real birds. In 8 or 9 days, the young birds abandon the nest and spend their remaining two-week preflight days clambering about among the branches. In late summer, the juveniles are molting into their first winter plumage, which closely resembles that of the adults. Nestlings have been recorded in Massachusetts from May 31 to July 4, and dependent fledglings have been seen from June 9 to August 25 (TC, CNR, Meservey), but the ranges for these, as with the eggs, is probably greater.

Immature and adult Black-billed Cuckoos share the same diet, primarily caterpillars, including the very hairy species normally shunned by other birds. Fall Webworms, the larvae of Gypsy Moths, and other caterpillars that periodically infest our orchards and woodlands are all consumed in great quantities by the cuckoo. The birds appear to follow the infestations to some extent, becoming locally very common in the areas of greatest caterpillar havoc.

In Massachusetts, the autumnal migration of Black-billed Cuckoos stretches through September and October, but the birds become scarce toward the end of the latter month. In this season, cuckoos seem particularly partial to protected stands of saplings and tall shrubs, and can often be sighted upon a visit to a favorite coastal or river valley migrant trap. The species winters in northwestern South America.

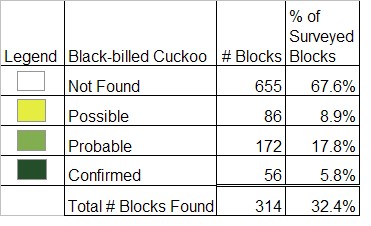

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: uncommon to common, preferring abandoned orchards and early second growth; numbers fluctuate from year to year

Brian E. Cassie