Breeding Bird Atlases (BBA)

Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

Herring Gull

Larus argentatus

Egg Dates

April 25 to August 8

Number of Broods

one; may re-lay if first attempt fails.

This abundant, large, gray-mantled gull is no doubt the most well-known coastal bird in the northeastern United States. Formerly restricted to breeding sites along the seashore, it now nests on inland lakes and reservoirs given the opportunity. Islands are the preferred nesting domain of this omnivorous larid, and the substrate may be rocky or sandy. A dependable food source is the main influence on its distribution, and it may range from an inland garbage dump or coastal beach to an estuary or the waters surrounding an offshore fishing fleet.

The first Massachusetts Herring Gull nest was discovered on Martha’s Vineyard in 1912. Subsequent breeding occurred in 1919 on Skiff’s Island, an ephemeral sandbar off southeastern Martha’s Vineyard. In 1925, Forbush doubted that the Herring Gull could survive as a breeding species in the face of a growing human population and increased beach recreation. However, the Herring Gull took hold, and the population gradually increased until the late 1940s, when it exploded. The increase began to level off in the mid-1960s, and the numbers have remained static since then. (The estimated Massachusetts population was 36,250 pairs in 1972 and 35,750 pairs in 1984.) The Herring Gull population has stabilized, apparently due at least in part to competition with Great Black-backed Gulls on nesting islands. Laughing Gulls and terns have declined as the more aggressive large gulls crowd them from favored nesting areas and prey on their eggs and young. In addition to its coastal colonies, the Herring Gull was also confirmed nesting inland at the Wachusett Reservoir. Breeding at the latter site was first detected in 1965, when 800 adults and 30 flightless young were estimated on July 25. The colony peaked in 1967, with 500 pairs. In that year, the Metropolitan District Commission initiated a gull-control program, collecting and removing the eggs. This policy has proved to be effective, and only a few pairs have nested there in recent years.

The loud buglelike feeding and territorial calls of this raucous bird are well known. Vocalizations are variable on the feeding grounds, while a low throaty ow, ow, ow is the common call of an adult soaring overhead. In mid-April, adult Herring Gulls (age four and older) begin using an extensive repertoire of displays and vocalizations to establish their breeding territories. When pair formation is concluded, nest building begins. The nest is built of dry grass obtained from the immediate vicinity and is constructed by both birds. It may be in the open or concealed neatly in a clump of Dunegrass or other vegetation. As is the case with most colonial seabirds, a strong bond exists between the parents. Appeasement displays are continued throughout the nesting period, and both birds share the duties of incubation and caring for the chicks.

The clutch of eggs usually numbers three, although a nest of two or four is not uncommon. Peak egg laying in Massachusetts occurs from May 3 to May 30 (Nisbet, Drury). Cryptically colored, the eggs range from olive to dark brown to tan with irregular dark blotches. The chicks hatch after an incubation period of about 26 days and are precocial. They seek shelter in nearby vegetation 3 to 5 days after hatching and are fed regurgitated fish, crabs, and various bivalves. The average pair raises one or two young to fledging age (Nisbet).

As autumn approaches, the chocolate brown fledglings may be seen accompanying the parents to the feeding areas. Later, juvenile Herring Gulls migrate to wintering grounds that extend from the mid-Atlantic as far south as the Florida and Gulf coasts and beyond. The adults, for the most part, remain to winter in New England, although some may move south to the Connecticut and New Jersey shores.

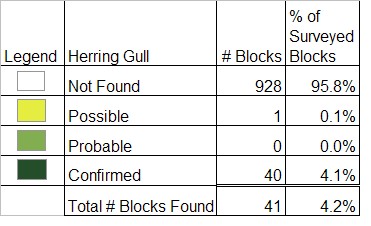

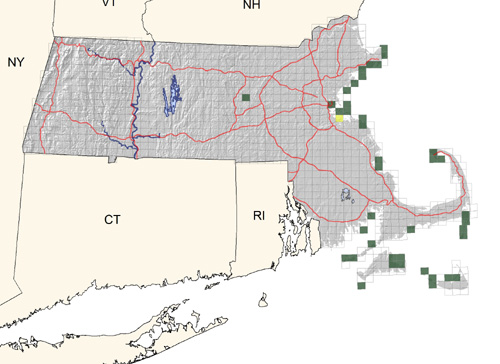

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: abundant on offshore islands, also inland at Wachusett Reservoir; declining

Peter Trull