Breeding Bird Atlases (BBA)

Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

American Oystercatcher

Haematopus palliatus

Egg Dates

April 22 to July 4

Number of Broods

one; may re-lay if first attempt fails.

One of the state’s most spectacular birds, the American Oystercatcher, is a fairly recent addition to Massachusetts’ breeding avifauna. However, its appearance is more a matter of reestablishing itself in territory once occupied than a bona fide range extension. Oystercatchers were apparently common in this area during the early 1800s (and Audubon claims to have seen them as far north as the Saint Lawrence River), although it is not known if they nested during that period. In any event, by the mid-1800s they had disappeared from the entire Northeast, due in part to excessive hunting; and the species remained a rare vagrant until the mid-1900s. With protection, oystercatchers gradually began to reclaim some of their former range, and in 1969 a pair nested on Martha’s Vineyard, establishing the first confirmed breeding record for the state. By 1984, the Massachusetts population had increased to an estimated 42 pairs.

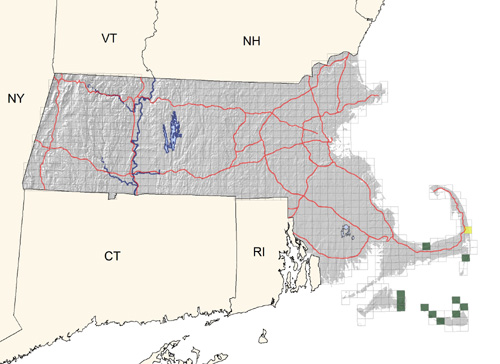

In Massachusetts, nesting oystercatchers are found almost exclusively on the islands off the southern coast—Monomoy, Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard, and the Elizabeth Islands, where they inhabit sandy beaches and salt marshes adjacent to the tidal flats where they feed. Oystercatchers are among the earliest residents to appear on our coastal beaches, often arriving by mid-March if the weather is mild. Soon after, they begin to establish territories, often with the same pairs occupying the same sites as in previous years. Some pairs defend a single territory that contains both nesting and feeding areas, while others have disjunct nesting and feeding territories that may be separated by as much as several hundred yards.

Oystercatcher vocalizations are complex and varied, particularly during the breeding season. A frequently heard call is a loud, ascending wheep, often given in flight. A loud piping note, given singly or in series, is also common. Courtship and territorial displays are elaborate and noisy affairs that can best be described as comical and that involve exaggerated posturing, display flights, and various displacement activities, all accompanied by loud, rapid calls. Birds from neighboring territories as well as nonbreeding immature individuals (up to three or more years old) often become involved in these performances, resulting in chaotic scenes.

The nest, merely a shallow depression in the sand or dry marsh grass, is located along the dune or marsh edge or on an elevated ridge within the marsh. Each year, a few nests that are elevated inadequately are lost to the spring tides, in which case the pair usually renests. Clutch size ranges from two to five eggs, although the majority of nests contain three eggs; nests with five eggs may be the result of 2 females laying in the same nest.

Incubation lasts about 27 days and is performed by both parents. During this period, the appearance of a human intruder, even at considerable distance, causes the incubating bird to quietly leave the nest, while both parents anxiously wait nearby. Potential avian predators such as gulls, crows, and harriers, on the other hand, are attacked vigorously.

As for all shorebirds, the young are precocial and soon after hatching are led by the parents to the security of denser vegetation near the pair’s feeding territory. However, unlike most shorebirds, young oystercatchers are totally dependent upon the adults for food, and not until they are several months old are they able to fully feed themselves. The chicks are remarkably adept at hiding in the marsh grasses, and until they reach fledging age at about 35 days are extremely difficult to find. Nonetheless, normally only a small percentage of chicks survive to fledging.

By midsummer most of the surviving young have fledged, territorial defense wanes, and the species’ gregarious tendencies increase as family groups begin to gather in flocks of 10 to 30 or more birds. By early October, most oystercatchers have left for their wintering grounds along the mid-Atlantic coast, though a few stragglers occasionally linger into early November, and rarely December.

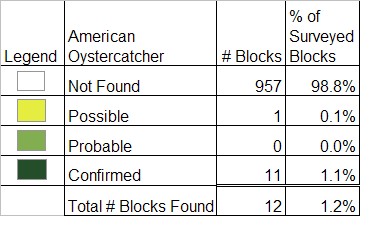

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: uncommon and local on the outer Cape and Islands; increasing

Blair Nikula