Breeding Bird Atlases (BBA)

Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

American Black Duck

Anas rubripes

Egg Dates

March 20 to late July

Number of Broods

one; may re-lay if first attempt fails.

Historically, the common dabbling duck of the inland waters and salt marshes of Massachusetts was the American Black Duck. Black ducks were abundant throughout the Northeast, which was outside the traditional breeding range of the Mallard. Popular with waterfowlers for the past 200 years, the wary black ducks withstood even the pressures of market hunting and spring shooting. However, they have not been able to withstand the changes wrought by modern America.

Black ducks still nest widely in the state, but the numbers have been declining throughout their range since the mid-1950s. Much of the early drop was due to loss of both breeding and wintering habitat. In Massachusetts, 50 percent of the shallow freshwater marshes existing in 1951 were gone by 1971, while many deep marshes were dammed to create open ponds. Coastal marshes have not fared any better and have been victim to shortsighted exploitation. The situation has been made more critical by the invasion of undesirable Common Reed into much of the remaining habitat.

Extensive use of pesticides to combat mosquitoes, Spruce Budworms, and Gypsy Moths has occurred throughout the black duck’s range, including Massachusetts. Other environmental contaminants are commonplace; the effects of acid rain on waterfowl are yet to be researched fully. Hunting pressure, especially in Canada, increased greatly during the 1970s but has slacked off since then. Urbanization, to which the Mallard readily adapts, is a major threat to this species.

The Mallard currently poses the greatest threat to the American Black Duck. The two species are closely related and have nearly identical calls and displays. They hybridize freely, producing fertile offspring. Over time, the Mallard is threatening to swamp the gene pool of the black duck. The situation has become more critical as Mallard numbers continue to increase (see account for that species). In Massachusetts, Division of Fisheries and Wildlife personnel determined that 15 percent of the black ducks they band along the coast during the winter show signs of hybridization. The actual proportion could be twice that. As wetland habitat in the Northeast continues to succumb to the deleterious effects of urbanization and Mallards proliferate, the future of genetically pure American Black Ducks is in jeopardy.

Breeding from Beaver ponds to salt marshes, the black duck is a territorial bird. The aggressive male will not permit another conspecific pair to nest on a pond he has claimed as his own. The exception is when ducks nest on islands. Perhaps this behavior is related to his drab coloration. For whatever reason, black duck nesting densities are lower than those of other duck species.

Nests are generally located under cover of wooded thickets, conifers, or thick herbaceous growth. In areas subject to flooding, black ducks have adapted to nesting on stumps, snags, or low tree crotches and cavities. Egg laying in Massachusetts begins in late March. Clutches range from seven to twelve eggs and are laid in scrapes lined with vegetation. Most of the dark down is added during the latter stages of egg laying and is used to cover the eggs when the hen is off the nest. Incubation is about 26 days, depending upon nest attentiveness and air temperatures. In a Quabbin study, the earliest broods appeared about May 10, and the last hatched July 7. Only about half the nests are successful, but black ducks readily renest, although they typically do not initiate clutches as late in the season as will hen Mallards. Females lead their broods to water, where the ducklings feed on insects and other invertebrates, later switching to plant foods. Generally, black ducks consume more animal matter than Mallards. In Quabbin, broods averaged seven ducklings (range four to twelve) on the date they were first seen and averaged five ducklings (range four to twelve) on the last date seen. The young first fly at about 60 days old.

In the fall, few Massachusetts black ducks move south. Most shift to the coast for the winter, where they are joined in early December by other birds from Quebec and the Maritime Provinces. A factor in the survival of wintering American Black Ducks is the pronounced tide fluctuation that allows them to feed in the salt marshes at high tide and on mussel flats when the tide is low.

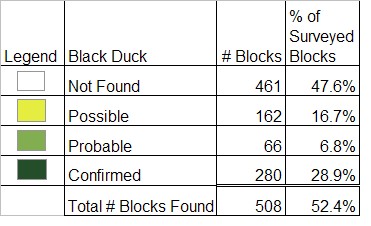

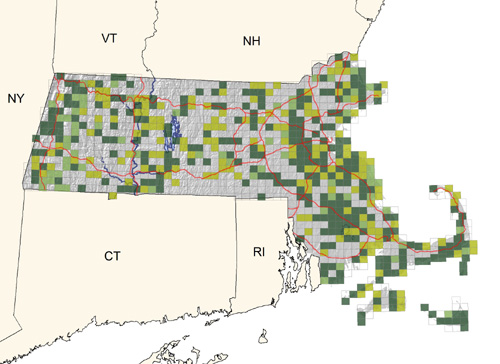

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: common and widespread breeder; very abundant migrant and very common winter resident, possible declining

H. W. Heusmann