Breeding Bird Atlases (BBA)

Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

Turkey Vulture

Cathartes aura

Egg Dates

early May to early August

Number of Broods

one

For the better part of this century, the Turkey Vulture was no more than a rare or casual straggler in the state, with the majority of sightings concentrated in southernmost Berkshire County. The first proven record of breeding occurred in this region at Tyringham, where a nest with two downy young was found on August 29, 1954. Nesting may have taken place as much as a decade or more earlier because an immature with down on the head and neck was found dead at Mount Everett in August 1945.

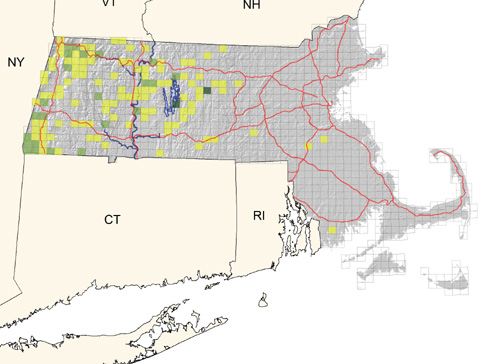

There has been a pronounced increase in the Turkey Vulture population since the early 1970s, and the species now breeds in northern Vermont and Maine. It is difficult to determine exactly where vultures nest in the state because of the birds’ wide-ranging flights in search of carrion and their reclusive nesting habits. These behaviors account for the preponderance of “possible” records on the map. Undoubtedly, vultures are much more common as a breeding species, although not necessarily more widely distributed, than the map would indicate. There were two confirmations during the Atlas period, one in Barre and one in Quabbin. From 1982 to 1987, eight nests were located in eastern Massachusetts in the Blue Hills Reservation in Milton (Smith), and in 1986 breeding was confirmed in Sturbridge.

The Turkey Vulture is most common from New Jersey southward throughout much of temperate and tropical America. Its splayed wing tips and long, two-toned wings held in a pronounced dihedral over the back are characteristic, as is the typical, leisurely, rocking flight as a bird courses over field and treetop. Although it prefers not to fly on cloudy days or during strong winds, the “Buzzard” (as it is known south of the Mason-Dixon line) is fully capable of flying with deep, slow wing beats, but its soaring flight uses less energy. The birds are generally silent, except for occasional hissing and growling sounds used near the nest.

The first spring migrants normally begin appearing in early March, but they may arrive as early as mid-February with unseasonably warm weather. Reports formerly were concentrated in central and western Massachusetts, but migrants are now seen throughout the state, including outer Cape Cod.

Pairing, which may involve dancing antics of groups of birds on the ground, apparently occurs during late April or early May. All known nest sites in Massachusetts have been located in caves or crevices, or on shelves of rocky ledges on hillsides, but in other regions they may be in hollow logs, tree stumps, old buildings, or on the ground. No nest materials are used. Clutch sizes range from one to three (average two), and for 7 Massachusetts nests were as follows: one egg (3 nests), two eggs (3 nests), and three eggs (1 nest) (Smith). The Barre nest contained eggs on June 22 (Cardoza). The elliptical eggs are creamy white and blotched with varying shades of brown. The incubation period is not known precisely but generally is considered to be five to six weeks. Both sexes incubate and feed the young by regurgitation for eight to ten weeks. Predators are often attracted to the malodorous nest site; hence the need for inaccessible and remote locations because the adults are virtually helpless in defending the eggs or young. Of the 8 Blue Hills nests, 1 was abandoned and 4 were lost to predators, probably Raccoons. The other 3 nests fledged one young each (Smith). Predators also destroyed the Quabbin nest during the Atlas period. On July 30, the Sturbridge nest contained two young.

By late summer, vultures become increasingly conspicuous as immatures augment the adult population. The southbound migration occurs from mid-September to mid-October, but an increasing number of sightings are made in late fall and early winter. Breeding residents probably winter in the southern United States, although, concurrent with the population increase in the Northeast, winter roosts have become established as far north as Connecticut. It seems probable that a small population of permanent residents will become established in the Quabbin area, where the breeding population is high and where deer carcasses would be available to sustain them through the rigors of winter.

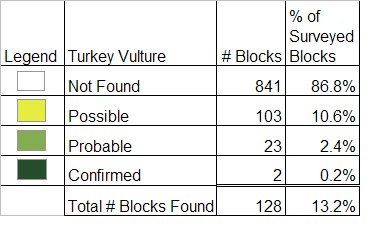

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: uncommon in hills of central and western regions; increasing throughout the state

Richard A. Forster