Breeding Bird Atlases (BBA)

Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

Black-crowned Night-Heron

Nycticorax nycticorax

Egg Dates

first week of April to third week of July

Number of Broods

one; may re-lay if first attempt fails.

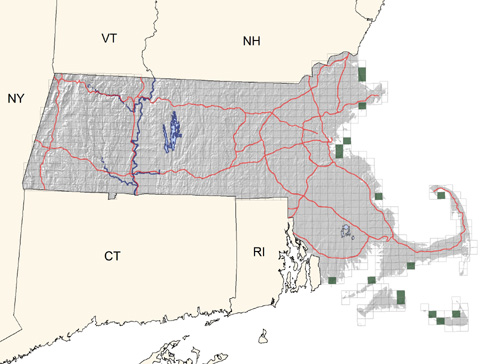

One of the best known of its tribe, the Black-crowned Night-Heron is widely distributed in coastal Massachusetts. At one time it was the most abundant heron, but recently its population has suffered a dramatic decline. From 1915 to 1920, there were more than 3,000 birds in three colonies; in 1955, there were 3,600 in ten colonies; in 1975, there were 1,894; in 1976, there were about 1,500 in fifteen colonies; and in 1977, there were 1,958 birds in fourteen colonies. During the 1950s, many heronries were shot out or dynamited because the birds were considered noisy and smelly neighbors. Pollution, DDT contamination, and the steady loss of habitat from coastal development have also contributed to the population decline.

Black-crowned Night-Herons forage in coastal salt marshes, freshwater marshes, ponds, creeks, and tidal flats. They are primarily nocturnal and crepuscular feeders, roosting by day in the vegetation bordering wetlands. Food items include fish, amphibians, insects, crustaceans, and sometimes the young of gulls and terns. The common call of this species is very distinctive and is the origin of the common name of “Quawk.” The call may be uttered as the birds fly to and from their roosts or when they are disturbed.

Black-crowned Night-Herons usually arrive in mid-March. They are colonial breeders, often nesting in mixed-species heronries. Males claim and defend small nest territories and use several ritualized displays including “upright display,” “forward display,” and a “bill snapping display” (Palmer 1962). Courting males land near a female and bow toward her while raising the head plumes and fluffing out the breast, neck, and back feathers. This display may be followed by bill touching.

Nests are usually built in trees or shrubs from 2 to 42 feet above the ground. At Clark’s Island, most pairs nested above 10 feet in Red Cedar. The birds’ excrement generally kills the vegetation, and eventually the nesting area must be relocated. The nests are crudely constructed masses of sticks and twigs arranged rather haphazardly, with little in the way of lining to form a soft inner pocket. The three to five pale bluish green eggs are usually laid in late April or May. After 24 to 26 days of incubation, the young hatch and are cared for by both parents. Food consists of predigested juices at first, followed by partially digested fish, frogs, and crabs. The adults remain with the young for two to three weeks, until they are about two-thirds grown. At this age, the juveniles begin to climb about the nest site, using their feet, wings, and neck. This is a precarious time for young herons, and many fall to a premature death. Fledging occurs at from six to seven weeks of age. In 1975 and 1978 at Clark’s Island, average pairs reared two or three young to at least 10 days of age. This is considered to be good nesting success.

Adults and juveniles disperse far and wide from the nesting colonies beginning in mid- to late July. They most often gather in seaside roosts near favorite feeding areas. Throughout October and November, most depart for wintering grounds in the southern United States and beyond. Some individuals linger until early December, and a few overwinter along the Massachusetts coast.

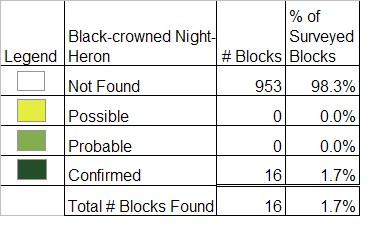

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: locally common on coastal islands; historic numbers greatly reduced

Robert Prescott