Breeding Bird Atlases (BBA)

Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

Great Egret

Casmerodius albus

Egg Dates

first week of May to third week of June.

Number of Broods

one; may re-lay if first attempt fails.

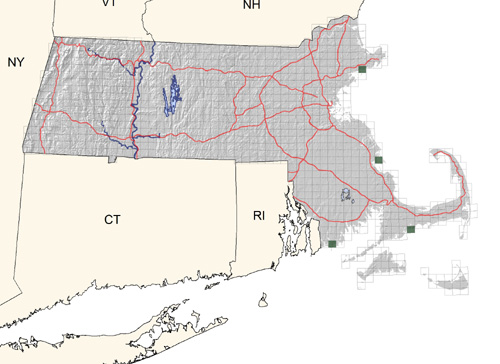

Since the turn of the century, when this species was nearly exterminated in North America by the plume hunters of the millinery trade, the Great Egret has increased steadily in number. During the first half of the century, Great Egrets were occasionally seen in Massachusetts during the late summer and fall and were presumably post-breeding dispersal birds. In 1954, a pair nested in a cedar swamp in South Hanson. Since then they have nested in small numbers at scattered locations along the coast. During the Atlas period, there were breeding records from four sites, with the largest number of birds being 10 pairs at Clark’s Island in Plymouth Bay. Smaller numbers were also recorded at House Island in Manchester, Ram Island in Westport, and Sampsons Island on the southern shore of Cape Cod.

Great Egrets begin to arrive in early April, when they can be seen feeding in marshes near their breeding areas. They forage in ponds, tidal inlets, marshes, damp meadows, swamps, and other wet habitats, usually in deeper water than smaller egret species; and they will defend a feeding territory. Great Egrets forage by walking slowly or standing, usually with an upright posture. Occasionally, they will walk quickly or hop between feeding areas, and they may hover and plunge into the water. They feed mostly on fish but also take insects, frogs, salamanders, and small mammals.

In Massachusetts, most Great Egrets are nesting by mid-May. They are colonial breeders, joining mixed-species colonies of Snowy Egrets, Little Blue Herons, Black-crowned Night-Herons, and Glossy Ibises. At Clark’s Island, they have nested in Highbush Blueberry and Pitch and White pines, always on the very top of the bush or tree. Males defend a display territory using a “forward threat display” (Palmer 1962) in which all the plumes are erected. The well-developed aigrettes are displayed prominently in both hostile and pair-forming interactions. Aerial chases and advertising “circle flights” (Palmer 1962) are common. Courtship displays include the “stretch display” (Palmer 1962) in which the bird points its bill upward and swings its fully extended neck backward. The “snap display” (Palmer 1962) consists of a downward extension of the head and neck, during which the egret claps its mandibles together. Great Egrets make a variety of harsh single-syllable calls in hostile interactions. The advertising call is a soft frawnk. The birds have a repetitive rrreee call, which they make during greeting ceremonies at nest relief.

The nest is a loosely woven platform of sticks and twigs up to approximately 3 feet in diameter. Great Egrets have been known to reuse old nests that have remained intact over the winter. The eggs are light bluish green, usually three to four in number. The incubation period, shared by both parents, is slightly more than three weeks. Incubation commonly begins with the second egg, and hatching is asynchronous, producing a brood of chicks of differing sizes. Often the smallest chick starves or is killed by its siblings. The chicks are covered with white down and have bright yellow bills. When they are three weeks old, the chicks are able to climb about in the nest tree. They fledge at about six weeks of age. At the Clark’s Island heronry, nesting success in 1975 and 1978 was good, with each pair of Great Egrets raising at least one chick and some rearing two young.

Great Egrets show some northerly postbreeding dispersal and gather in communal nocturnal roosts with other herons in late summer (e.g., Plum Island). They may occur at inland swamps and ponds as well as on the coast. East Coast birds winter from North Carolina south to the Bahamas and the Antilles.

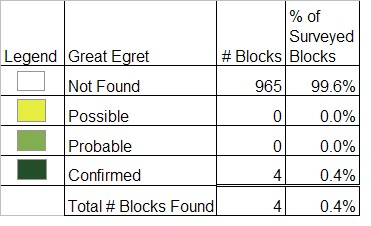

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: rare and local; usually associated with larger coastal heronries, recently increasing

William E. Davis, Jr.