Breeding Bird Atlases (BBA)

Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

Great Blue Heron

Ardea herodias

Egg Dates

April 15 to June 12

Number of Broods

one; may re-lay if first attempt fails.

The first well-documented nesting of the Great Blue Heron in Massachusetts occurred within the Harvard Forest, Petersham, in 1925. This colony of up to 20 nests survived, shrouded in utmost secrecy, until its destruction by the hurricane of 1938. Subsequent to the demise of the Petersham heronry, small colonies likely persisted in remote rural areas prior to the Atlas period, but their presence went largely unnoticed, and they were little known to the general public.

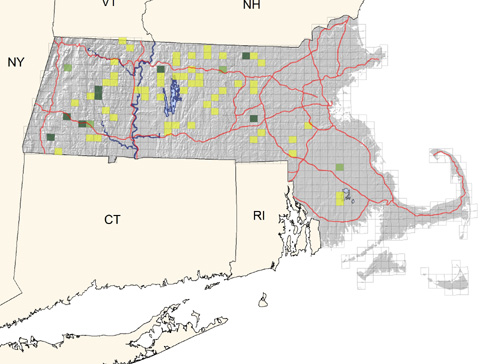

During the Atlas period, 8 nesting sites were found from Westboro and Townsend to Sheffield and Otis in the Berkshires. Some 52 “possible” nesting sites reported in the period appear to be more a reflection of the large number of wandering individuals than actual colonies. Since 1979, the nesting population seems to have grown in size and expanded considerably. In 1984, a total of 229 nests were counted among 23 active heronries that ranged in size from 1 to 48 nests. As of 1984, “confirmed” colonies were distributed quite broadly across the state from a north-south line connecting Dunstable, Maynard, and Norfolk westward, with a distinct center of abundance in Worcester County.

The Great Blue Heron frequents all aquatic environments, including the shallow waters and shores of lakes, ponds, and waterways. It visits coastal beaches and marshes, tidal flats, and sandbars. Shy and wary during the nesting season, it retires into inland backwaters, swamps, and Beaver impoundments, usually away from populous areas. It does not nest communally with other herons in Massachusetts as is frequently the case in the southern United States. In Massachusetts, the recent increase and expansion seems linked to extensive Beaver flowages and associated fisheries that have gradually developed in the state since the return of the Beaver in the mid-1950s.

Nest sites here seem to be predominantly in dead trees drowned by impoundments, especially those created by Beavers. Nests are also found occasionally in living oaks or White Pines. After several years, depositions of excrement tend to burn back leafy vegetation, and trees eventually become sickly. Nests are massive stick platforms 30 to 60 feet above the ground and are repaired and reused annually. Occasionally, a pair of Great Horned Owls will appropriate a platform before spring reoccupation by the herons, but the owls’ presence seems to be benign and entirely ignored by the herons.

Spring occupation of heronries begins in mid-March and continues well into April. Nest building and repair commences almost immediately upon arrival. Great Blue Herons engage in highly ritualized breeding behavior. Males initially defend a display site, usually an existing nest. Defended territory is confined to the immediate vicinity of the nest. Territory is used for pair formation and maintenance, copulation, nesting, and rearing of young. Mutual preening and billing by adults are thought to cement pair bonds, which are monogamous for at least seasonal duration. Promiscuous behavior is sometimes observed. First-year birds frequent colonies, sometimes in small visiting parties, but do not normally breed until their second year. Yearlings often occupy sites and build practice nests. These nests are usually flimsy affairs but occasionally are well developed and used as a nest foundation in subsequent seasons.

Clutch size ranges from three to seven (usually four) eggs. The range of mean brood size in Massachusetts (third week of June 1980 to 1984) was 2.2 to 2.9. One egg is laid every other day, and incubation starts after the laying of the first egg, as early as April 15. Both sexes incubate, and nest relief is often accompanied by presentation of sticks and other rituals. The incubation period lasts 25 to 29 days, with re-laying occurring until mid-June.

These herons are generally silent, but sometimes, especially when startled, they give an assortment of low-pitched hoarse croaks or a cranky bark. Birds are sometimes quite active and noisy at night. Nestlings keep up a constant guttural chatter that rises and falls as they are excited by the arrival of adults with food.

For the first two months, the young remain in the nest and are dependent on the parents, both of which tend the young. They gradually become more adventurous, stepping out onto the rim of platforms and nearby limbs. The first flights occur at 55 to 60 days. Young return to the nest at night, sometimes for up to three weeks, but abandonment is usually complete by 85 to 90 days, when dispersal of young in all directions begins. These wanderings last until mid-September.

Fall migration occurs from mid-September through late October. Most lingering individuals move southward upon the arrival of more severe weather, but small numbers winter regularly about Cape Cod and the Islands, casually even farther north and inland, open water permitting.

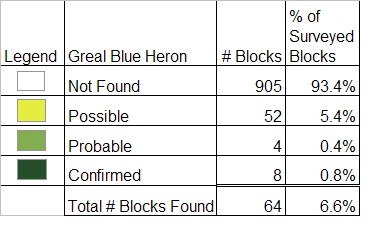

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: uncommon and local at inland wooded swamps (especially Beaver ponds); recent increase

Bradford G. Blodget