Breeding Bird Atlases (BBA)

Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

Virginia Rail

Rallus limicola

Egg Dates

early May to late July

Number of Broods

one; may re-lay if first attempt fails.

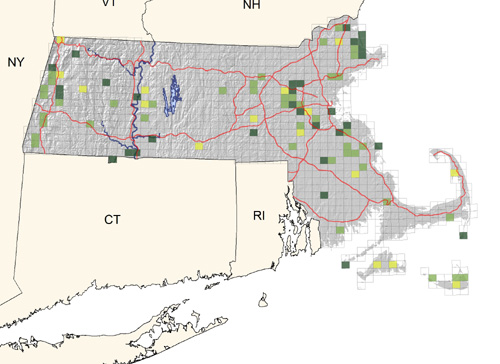

The Virginia Rail is an inconspicuous and somewhat local summer wetland resident whose abundance is largely determined by the availability of suitable breeding habitat. Preferring extensive cattail marshes for nesting, it will also breed along the brushy banks of open river meadows and occasionally around the vegetated margins of undisturbed suburban ponds. The species is notably local as a breeder in central Massachusetts, as well as on the Cape and Islands. South of New England, it is not uncommon as a nesting bird in the upper portions of coastal salt marches, but in our area it is unusual in such situations.

The spring arrival of Virginia Rails from their southeastern wintering grounds generally takes place during the last half of April, with their return apparently contingent on local weather conditions and on appropriate water levels in their chosen breeding marshes. Because of their retiring nature, much of our knowledge of their precise migration timetable must be derived from their vocalizations. These calls, many of which are not well understood, are given irregularly, often at odd hours of the evening. Additionally, it is probable that many individuals may not call immediately upon their arrival, further making it difficult to pin down their migration schedule.

A dawn visit to an appropriate breeding meadow on a mellow and windless May morning is most likely to produce a chorus of territorial male Virginia Rails. In this season, the advertising calls of the males are a metallic-sounding ki-dik, ki-dik, ki-dik, with distance distorting the call and making it sound more like dik, dik, dik. This vocalization is given with considerable energy, and it often continues uninterrupted for many minutes. A second common call, and one not confined to the breeding grounds, is a piglike grunting sound, which ends with a diminishing quality, much like a bouncing ball coming to a stop. Phonetically, it may be rendered as wak-wak-wak-wak-wak. It is likely that this call is shared by both sexes. While the advertising call of the male is rarely heard after early June, a third and less frequently heard vocalization is occasionally given in this season. Best described as kic-kic-kic-ki-queeah or tic-tic, McGreer, this call may be given by female rails in search of a mate or as a contact call to a straying mate. Adult rails utter a variety of specialized vocalizations, presumably to communicate with their young. Most remarkable of these sounds is a low, guttural growl, ka-ka-ka-ka-ka-ka, which is apparently used when the chicks are in jeopardy.

By May, some Virginia Rails are laying clutches of five to twelve buffy-white eggs, which are sparsely speckled with reddish brown. Their well-concealed nests may be placed on the ground amidst marsh vegetation, in a grass or sedge tussock, or among plants over mud or water. The nest is usually constructed of course grass, dead stalks, cattails, or other plant materials. Incubation is shared by both sexes for a period of 20 days. There seems to be considerable variation in the timing of nesting, with egg dates in southern New England ranging from early May to early August. Once the glossy, greenish black, precocial chicks hatch, they leave the nest and accompany both parents about the marsh, much in the fashion of tiny chickens. In Massachusetts, there are 19 records ranging from May 27 to July 29 that pertain to adults with young. Single birds or pairs were observed tending from one to five chicks (BOEM).

By late summer and early fall, Virginia Rail populations are at their peak in the marshes, and, in this season, a few are hunted legally by sportsmen who are willing to take the trouble to find them. With each autumn cold snap, the numbers lessen as more birds head south. By November, only a hardy few are left to winter, primarily in southeastern Massachusetts, wherever they can find an open spring-fed seep, running brook, or salt marsh along the coast. The main wintering grounds extend from the southern states to northern Central America.

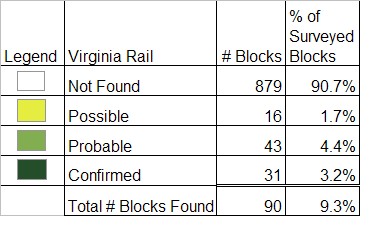

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: uncommon to locally common in freshwater and brackish marshes

Wayne R. Petersen