Breeding Bird Atlases (BBA)

Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

Ruffed Grouse

Bonasa umbellus

Egg Dates

early April to late June

Number of Broods

one; may re-lay if first attempt fails.

The Ruffed Grouse, symbolic of New England, is found throughout Massachusetts, breeding from the western Berkshires to the Pitch Pines of Cape Cod. Populations in Massachusetts were highest during the period between the Civil War and World War II, when much of the state was farmed and the interspersion of woods, fields, and edge made excellent habitat for nesting and feeding. As Massachusetts forests matured, grouse numbers began to decline, and, although the species still occurs throughout the state, the populations of the early 1900s will never return.

The grouse has no equal as an upland game bird. The thunderous takeoff and quick escape enable it to easily outwit or unnerve most hunters. The grouse eats mostly fruits, nuts, berries, and leaves, and much of its life is spent walking rather than flying, so the breast meat is very tender and flavorful.

Grouse are nonmigratory, living out their lives on a few hundred acres. Their unique breeding ritual begins in the spring, with the male selecting and defending one or more drumming sites within his territory. He uses these locations to make the thumping sound so often heard in the spring in New England. Studies in the Quabbin-Hardwick area based on drumming counts showed spring densities of one grouse per 10.1 to 21.6 acres. A cock drums by sitting back on his tail and beating his wings as rapidly as possible for a few seconds. The noise has two very different purposes: advising females of his presence and warning intruding males to stay away. Females crossing this territory are courted actively with much strutting, and, once bred, the hen alone is responsible for ensuring the continuity of the species. The female does all the nest building and incubation, and it takes care of the young.

Vocalization is not the grouse’s strong point. That is probably why drumming is used to indicate territory. An alarmed grouse gives a rather sharp quit-quit call. A hen may call crut-crut-car-r-r to her young and also may squeal when defending them.

The nest is usually in heavy cover in thick woods at the base of a large tree. The eight to sixteen buff-colored eggs are laid in early to mid-April in Massachusetts, with hatching about 23 to 24 days after the last egg is laid. If the first clutch is lost, the hen may lay a slightly smaller second set of eggs. The precocial young begin walking and foraging hours after hatching. At 10 to 12 days of age, they can fly well enough to roost in trees. Dates from eastern and central Massachusetts for 37 broods of young range from May 7 to July 25 with most (26) recorded during June. Brood size ranged from two to fifteen chicks (BOEM, TC).

The hen, a devoted parent, will charge an unwary human who ventures too close to her young. Her other protective action is decoying the intruder by feigning a broken wing and uttering shrill crying noises while moving away from her chicks. Spring is a critical time for the young because long periods of cold, rainy weather can take a heavy toll on them. Owls, hawks, Red and Gray foxes, and Bobcats all feed on grouse occasionally, but, despite its many enemies, the bird has endured. Ultimately, the presence or absence of suitable habitat will determine the grouse’s future. It certainly has the resilience needed to survive.

As the young birds grow and spring eases into summer, they become more independent, remaining together mainly for feeding and roosting. In the fall, the young males, responding to a hitherto unknown urge, begin dispersing to establish themselves on new territories. This is the fall shuffle we often hear about, and the immature males may crash through picture windows or walk unconcerned through “village and farm.” In spite of the peculiar behavior, in spring most drumming sites are occupied, either by the traditional resident males or by new ones that have taken their places.

Although winter separates fall shuffle from spring drumming, grouse are well adapted for survival because the scales on their feet grow into “snowshoes.” Deep snow poses no obstacle, and, on cold, blustery nights, snow is actually an advantage because grouse will fly right into soft snow to escape overnight cold. Otherwise, thick conifers provide adequate protection. Winter food is mostly buds, with aspen and apple being favorites. When spring returns, the New England hills again echo with the drumroll of the male Ruffed Grouse.

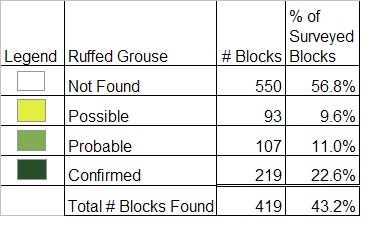

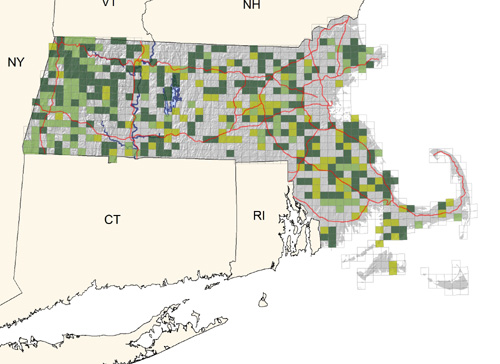

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: fairly common in woodlands with dense undergrowth; scarcer on the Cape and absent on Nantucket

Paul R. Nickerson