Breeding Bird Atlases (BBA)

Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

Brown-headed Cowbird

Molothrus ater

Egg Dates

May 14 to July 1

Number of Broods

brood parasite

The Brown-headed Cowbird, which lays its eggs in the nests of 210 North American birds (Welty & Baptista 1988), and the Bronzed Cowbird are the only native obligate brood parasites in North America. Some ornithologists speculate that the parasitic habit in cowbirds developed because they followed roaming herds of buffalo over the prairies. Unable to remain in one place long enough for nest building, the females simply deposited eggs in any available nest. Conversely, the parasitic habit may have developed first and thus permitted this species the freedom to form an association with roving herds.

The Brown-headed Cowbird is an abundant and widespread breeder and migrant in Massachusetts that expanded its range eastward as the forests were cleared for agriculture, eventually occurring over all of New England and southern Canada. During summer, the cowbird is most numerous on farmland in the vicinity of cattle, roosting and feeding in large mixed flocks with starlings and other blackbirds. The food of cowbirds is chiefly grain and weed seeds, but roughly one-fifth of the diet is insects, spiders, and a few small snails.

Spring migrants arrive in late March or early April, often in company with other blackbirds. Forbush states that “cowbirds are free lovers,” that “the courtship is a happy-go-lucky affair,” and that they are “neither polygamous nor polyandrous” but “just promiscuous” and “entirely unattached.” However, more recently observers have found that a male cowbird will follow a given female and defend the space around her from conspecific intruders. The defended space is thus a mobile territory (Welty & Baptista 1988).Courtship behavior may occur on the ground or in a tree and begins when one or more males position themselves near a female and face her, fluffing their feathers to form a neck ruff and pointing their bills skyward. The performance culminates when the male arches his neck, spreads his wings, fans and elevates his tail, fluffs his feathers, and bows low. This performance is accompanied by a bubbly glug, glug, glee, which has a wide range of frequencies. Many males repeatedly return to favored display perches. Females are also vigorously pursued in flight by one or more males. These activities may continue through June.

In addition to the song of the bowing ceremony, another vocalization given by the male is a high, prolonged squeak followed by several shorter, lower-pitched sibilants: pseeee-tsit-sit-si. Call notes are a short chuck or kuk, a loud harsh rattle, a slightly trilled pre-e-ah, and a hissing tse-e-e-e (Saunders 1951).

Cowbirds may be observed in a diversity of habitats, wherever the nests of appropriate host species are found. What is required is a cup nest of an altricial species that produces eggs smaller than those of the cowbird. These factors will ensure that the foster parents will be capable of feeding and caring for the young cowbirds until they are ready to fly and feed on their own. The most common hosts are tyrant flycatchers, vireos, wood-warblers, finches, and sparrows. However, orioles, tanagers, mimids, thrushes, and a variety of other species may also be parasitized. Female cowbirds sometimes err in nest selection; eggs have been found in the nests of Mourning Doves, which feed their young on “pigeon milk,” and in the nests of Killdeer, whose own precocial young quickly depart from the nest. Some host species (e.g., American Robin, Blue Jay, and Gray Catbird) will often puncture and eject cowbird eggs. The Yellow Warbler buries the cowbird egg under a new nest and lays another clutch. Yellow-breasted Chats desert their nests if a strange egg is present.

Species parasitized by Brown-headed Cowbirds during the Atlas period included the Least Flycatcher, Warbling Vireo, Red-eyed Vireo, Hermit Thrush, Wood Thrush, Blue-winged Warbler, Nashville Warbler, Yellow Warbler, Chestnut-sided Warbler, Black-throated Blue Warbler, Yellow-rumped Warbler, Black-throated Green Warbler, Blackburnian Warbler, Prairie Warbler, Black-and-white Warbler, American Redstart, Ovenbird, Common Yellowthroat, Eastern Towhee, Chipping Sparrow, Field Sparrow, Song Sparrow, and Northern Cardinal (Blodget, Forster, Kroodsma, Meservey, Ober, Spector).

The female Brown-headed Cowbird locates a nest by watching it closely during its construction, making regular trips for inspection. This intense observation of nesting activity may be what stimulates egg production in the parasite. The female cowbird enters the nest in the early morning during the host’s absence, may spend up to 3 minutes checking the nest, and then, in a matter of seconds, deposits an egg. If the female is frightened off before completing this process, she does not give up but returns later to lay her egg. A host’s egg may be removed by the cowbird, not at the time of laying but during that day, or the day preceding, and then generally only if at least two eggs are present in the nest. One female cowbird may lay a total of four or five eggs (some authors say ten to twelve) in 1 or several nests at the rate of one per day. Sometimes two different cowbirds parasitize a single nest.

A cowbird egg hatches after 11 to 12 days, about 1 day ahead of the host eggs. The youngster grows rapidly and fledges in 7 to 8 days. In Massachusetts, nestlings or fledglings have been observed from June 5 to July 6 (Spector, Meservey).

There seems to be little doubt that the nesting success of the host species is lowered as a result of cowbird parasitism; indeed, the effects on small populations of declining species can be devastating. The nests of species such as the Chestnut-sided Warbler that frequently contained cowbird eggs during the Atlas period (Forster, pers comm) may have been significantly impacted.

After nesting, adult Brown-headed Cowbirds have a complete molt and gather in large flocks. Once the young have become independent, they begin to join these groups. From August to November, the immatures lose their brownish gray plumage and attain the adult plumage. Fall migration occurs from September to November. A varying number of cowbirds remain to winter in Massachusetts, but most individuals winter in the middle and southern states.

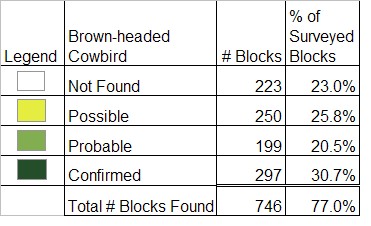

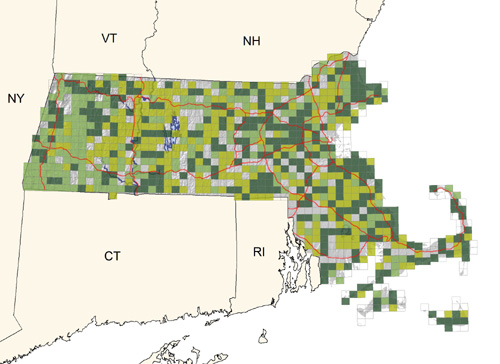

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: common brood parasite of smaller passerine species throughout the state

Dorothy Rodwell Arvidson