Breeding Bird Atlases (BBA)

Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

Winter Wren

Troglodytes troglodytes

Egg Dates

not available

Number of Broods

one; possibly two

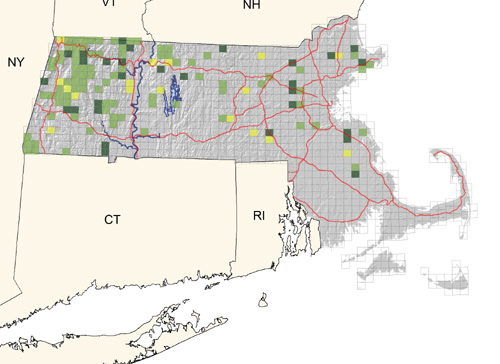

The Winter Wren is a jewel in the heart of the forest. Anyone who has seen this tiny, inquisitive bird and heard its ecstatic, sparkling song accompanied by a murmuring brook would be quick to agree. It is a regular migrant throughout Massachusetts and is best known as a breeder in Berkshire County and northern Worcester County. It is decidedly uncommon in eastern portions of the state and breeds only sparingly in Atlantic White Cedar swamps to the southeast. The Winter Wren is one of the least-known nesting birds in Massachusetts.

As winter retreats, early arrivals may be seen by the first week in April, but most migrants and breeding birds appear during the third week and continue through the second week in May. Its summer haunts are cool, moist, coniferous or mixed forests, where it frequents the edges of swamps, bogs, streams, and mountain brooks. In other seasons, it may be found in similar situations in deciduous forests. True to its scientific name, which means “caveman,” it spends its time bobbing about and investigating the roots of fallen trees, decaying logs, brush piles, tangles of low undergrowth, and mossy stumps and banks. It is there that it finds the varied insects upon which it feeds and also a suitable cavity in which to build its bulky nest.

The song of the Winter Wren almost defies description, although many have been written. It is a long, ebullient series of rising and falling notes and tinkling trills sung from near the ground or the top of a tree or dead stub. All day long and sometimes into the evening, its haunting song may be heard. The whisper song is a soft rendition of the full melody, and the alarm or call notes are an abrupt tick, chirr, or kip-kip.

Upturned roots of fallen trees seem to provide cavities most favored for nest building, although other nooks and crannies may be chosen. The well-concealed nest is made of mosses, small sticks, grasses, and rootlets. It is quite large considering the size of its maker, is shaped to fit the cavity, has a small entrance on the side, and is lined with soft feathers and animal hairs. Often, as with some other species of wrens, dummy nests are built, probably by the male.

Four to seven white eggs, sparsely to heavily dotted with brownish specks, are probably laid from May through July. Three Vermont egg dates range from May 24 to June 14 (Laughlin & Kibbe 1985). The incubation period is from 14 to 16 days, and the young leave the nest about 19 days after hatching. Early and late breeding dates indicate that two broods may be reared in a season, although this has not been positively recorded in Massachusetts. Both adults feed the young after they leave the nest. Encountering a family group of wrens on a mountain trail is an unforgettable experience. Like downy bumblebees, the young tumble away while the adults scold and buzz about. In Massachusetts, a pair with fledged young was recorded on June 19 (BOEM, TC).

The Winter Wren has been found taking shelter in barns and outbuildings and roosting with others of its kind in birdhouses. Because of its curious nature, it sometimes enters a closed camp through a small hole or crack and is unable to find its way out.

By September, a few will have started to migrate, but most will move south with the first cold weather in October through the second week in November. During the fall migration, this wren may be found in more open or even unexpected habitats, such as gardens and yards, and it may explore stone walls. There are reports of wintering wrens in southern Canada and the northern United States. In Massachusetts, most records in this season are from the coastal plain. Most individuals move to the southern states for the winter.

The Winter Wren is aptly named because it breeds in cool northern lati- tudes, such as Alaska, and because it winters in colder climates than any other wren species.

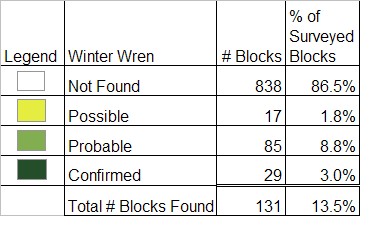

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: uncommon in higher elevations of the Berkshires; very uncommon and local in coniferous bogs and woodlands eastward

Martha H. McClellan