Breeding Bird Atlases (BBA)

Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

Cliff Swallow

Hirundo pyrrhonota

Egg Dates

May 22 to August 2

Number of Broods

one or two

No historical data on the Cliff Swallow is available, but it was probably represented in Massachusetts originally in small numbers about steep cliff faces. In the early nineteenth century, the species expanded its range throughout New England as it shifted from nesting at cliff sites to human-built structures. A slow decline, probably linked to the introduction of the House Sparrow, began after 1880. In this century, the decline has continued with the disappearance of buildings that have overhanging eaves preferred by the birds; the gradual loss of open agricultural lands; and, in some areas, general suburban-ization with its accompanying habitat loss, wetland filling, and pesticide use. In addition to these human-associated factors, the Cliff Swallow seems to be naturally vulnerable to prolonged periods of cold, rainy weather, when many are likely to starve to death.

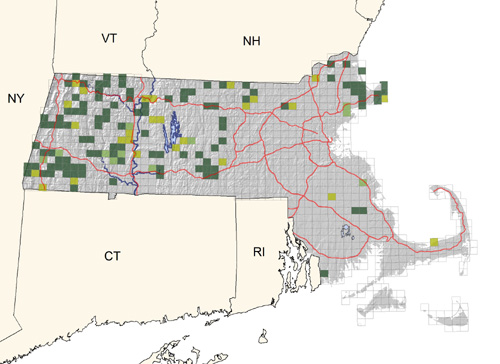

Perhaps, due in part to these factors, the Cliff Swallow, like the Purple Martin, has a puzzling, uneven distribution within its range and may be absent from ostensibly suitable areas while abundant at others. During the Atlas period, nesting was confirmed in nine of the state’s fourteen counties, with an overall sparse nesting distribution from Berkshire County generally eastward, sparingly into western and northern Worcester County, northern Middlesex County, and coastal Essex County. Except for isolated confirmations in two Plymouth County blocks, nesting was notably unrecorded in southeastern Massachusetts, owing, it is thought, to the sandy soil that is unsuitable for nest construction.

Although the Cliff Swallow is famed for its allegedly punctual arrival each March 10 at the mission of San Juan Capistrano in California, such regularity is seldom noted for this species in New England. Early arrivals are sometimes observed in late April, but general arrival at established colonies is usually in the first half of May. Late arrivals in June may be birds that have failed elsewhere and relocated, or birds whose migration was more protracted or began at a later date. Colonies, even large ones, can often exist undetected as birds remain close to these sites. Birds away from the colony are not particularly vocal but about their nests utter a constant social churring. The song is a series of unmusical creaking notes. When an intruder approaches the nests, the birds wheel about and protest with a loud, high keer alarm call.

The Cliff Swallow is highly colonial. Compared to western assemblages that sometimes contain thousands of birds, colonies in Massachusetts are small, ranging in size from 2 to 200 pairs, with few exceeding 100 pairs. The uniquely shaped nest is fastened to a vertical surface under wide eaves, such as on the sides of chicken coops, barns, or churches. The habit of building under bridges, common in the West, does not seem to have caught on widely in New England. More rarely, especially when there are wide doors, nests may be built inside a barn in close association with Barn Swallows.

Nest construction is usually underway in the third week of May. At several colonies in southern Worcester County, nests were under construction from May 14 to mid-July, with a peak from late May to mid-June. Some of the later nests were for second broods, but many represented renesting attempts. In cases of severe interference from humans and House Sparrows, the birds may relocate and build repeatedly. Both sexes participate in nest building, carrying mouthfuls of clay or mud to the nest site. Nest construction is accomplished in 5 to 14 days, with the speed influenced by weather conditions, mud supply, and amount of disturbance. House Sparrows, a menace at some colonies, attempt to appropriate nests for their own use, frequently breaking them in the process and resulting in disbandment of the colony. Nests resemble a gourd made of mud or clay pellets and are sometimes lined with fine grass or feathers. A necklike portion may protrude 5 to 6 inches or be absent altogether. Occasionally, when sheltered from the weather, the roof may be incomplete. Females have been reported to lay eggs before the nest is completed (which may account for some of these incompletely enclosed nests) and may lay an egg in the nest of another pair. If the building material is not of the proper consistency or the surface of attachment is too smooth, the nest may crumble or fall, especially as the young mature.

Clutches of three to six (usually four or five) eggs are laid. A Worcester County nest contained four eggs on June 3 (DKW). Both sexes incubate for 12 to 14 days. Young are fed by both parents and fledge at 23 days posthatching. They are fed for an undetermined period of time after fledging but presumably not more than a few weeks. Adults and young typically return to the nest to roost for a week or more. Once they have outgrown the nest, they will sit nearby or on it. Nestlings have been recorded in Massachusetts from June 10 to August 21 and fledglings from July 3 to August 21 (Meservey). Known fledge dates at a Charlton colony, where House Sparrow persecution was intense, were July 3, July 7, July 23, August 2, August 3, August 5, and August 21. Successful pairs typically reared two or three young, rarely one or four, to fledging age. Some pairs reared two broods, but most were forced to renest one or more times and produced only one brood. The latest nesters fledged young on August 21 and departed the same day (Meservey).

By the third week of August, southward migration is underway, and birds are seldom recorded after the first week of September. Cliff Swallows are diurnal migrants, moving south in small loose flocks but congregating in large numbers with other swallows at favored overnight roosting sites. Their migration path is remarkably long and eventually takes them to southeastern Brazil and central Argentina where they will spend the winter.

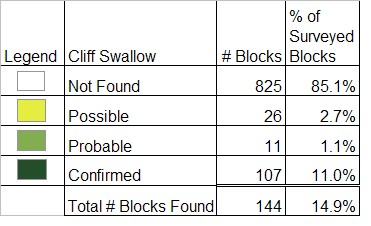

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: uncommon in small colonies in western regions, less common eastward; probably declining

Hamilton Coolidge