Breeding Bird Atlases (BBA)

Find a Bird - BBA1

Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Species Accounts

White-eyed Vireo

Vireo griseus

Egg Dates

May 22 to June 18

Number of Broods

one

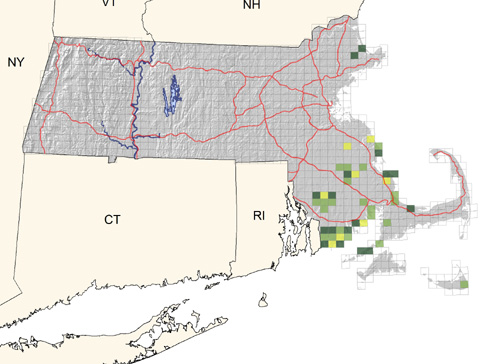

Massachusetts is at the extreme northeastern limit of the White-eyed Vireo’s breeding range, with the consequence that its population levels have fluctuated markedly in the last hundred years. Forbush plotted summer records in Massachusetts with the clear implication that until around 1880, White-eyed Vireos probably bred in all counties of the state except Dukes County. A rapid decline followed, and by 1955 the species was recorded only from Westport, where it was a rare straggler. The Atlas map still shows no breeding records from Berkshire County east to Middlesex and Norfolk counties. Compared with those of the late 1800s, populations of White-eyed Vireos are much reduced in Essex and Plymouth counties and remain as scarce as ever on Cape Cod and the Islands. The majority of confirmed breeding records are confined to Bristol County and the Elizabeth Islands. Thus, in the mid-1900s there was only a partial recovery of the 1800s range. Curiously, Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences’ spring and fall migration records showed no significant increases from 1971 to 1984, a period when other “southern” birds such as the Tufted Titmouse and Northern Cardinal were clearly increasing.

First spring migrants are seen in late April; movement peaks in mid-May, and birds are in breeding habitat before June. Migrants may be found in any fairly dense cover, usually close to the ground. White-eyed Vireos are persistent singers; indeed, the many “probable” records on the map emphasize that this species is more often heard than seen, even on nesting territory. Songs consist of five to seven loud notes, the first and last often a clear, emphatic chick, the middle notes slurred together and delivered rapidly. Individuals may have several songs or seasonal variations plus a variety of calls described as short ticks, whistles, and harsh mewing notes.

Nest sites are generally in moist areas or close to water, in thickets, shrubs, hedge-rows, tangles of vines, or briers. For an apt description, one can hardly improve on Forbush’s, “among the umbrageous foliage of bosky thickets.” The rather bulky nests are suspended in typical vireo fashion from a forked branch 3 to 7 feet above the ground. An outer construction of leaves, bark, and coarse material is lined with fine fibers, grass, or hair. In eastern Massachusetts, nests have been found in brier thickets in swampy areas, but also occasionally in upland pastures in barberry and other bushes. Other state nests include one found in Rehoboth, also on dry ground, at 20 inches in a cherry sapling growing in a thicket among Arbor Vitae and one at 3 feet in a clump of Arrowwood (ACB). Minute, sparse, dark speckles cover the four to five white eggs, which are laid from late May to early June and are incubated by both parents for 12 to 15 days. One state nest contained a single egg on May 26, and another contained four fresh eggs on June 6 (ACB).

Nest predation is a major mortality factor in thicket-nesting species; thus, it is interesting to note that a strategy has evolved to minimize the dangerous preflight period for juveniles. Fledgling White-eyed Vireos leave the nest before their flight feathers are fully grown, advancing the crucial fledging date by 1 or 2 days. The adults are aggressive and noisy when potential predators are in their territories, particularly when the young fledge. White-eyed Vireos are solitary nesters, and indeed extremely territorial, but may be quite frequently encountered in suitable habitats, e.g., five pairs breeding in 20 acres of the moist coastal thickets of Rocky Point, Plymouth. Little specific information is available about nestlings or fledglings in Massachusetts. Adults are observed carrying food in late June and early July, presumably for nestlings, and an adult and immature were observed together on July 17 (BOEM).

From mid-August until early Septem- ber, adults replace all plumage in a complete postnuptial molt. Juveniles disperse and wander during this same period, and they also molt all feathers except the inner five or six primary and six outer secondary wing feathers. Fall migration is from mid-September to early October. A few stragglers have been recorded in November, but none have been reported to overwinter in Massachusetts. Normal wintering areas are in dense vegetation from the southern United States to Cuba and Nicaragua.

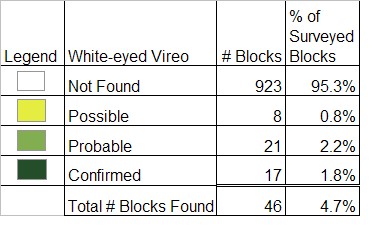

Map Legend and Data Summary

Atlas 1 data collected from 1975-1979

Note: locally uncommon in moist thickets of southeastern Massachusetts

Trevor L. Lloyd-Evans