Publications & Resources

Mass Audubon conducts research and produces reports on everything from land use to breeding birds.

Reports

Growing Solar, Protecting Nature

Mass Audubon teamed up with Harvard Forest to complete a comprehensive analysis of Massachusetts’ options for future solar development.

A Pathway to 30x30

This report makes the case for protecting natural and working lands and outlines how the Commonwealth can reach its 30x30 and 40x50 land conservation goals.

Losing Ground

A report analyzing changes to land use patterns in Massachusetts using the most up-to-date technology every five years.

Breeding Bird Atlases

Collection of data about all of the birds that breed in a particular state or region.

State of the Birds

Reports that analyze data as to how our bird populations had changed over time and what's projected for the future.

Publications

Action Agenda

An ambitious five-year plan that signals a dynamic new era for the organization.

Explore

Mass Audubon's Quarterly member newsletter.

Annual Report

A look at the past year's accomplishments.

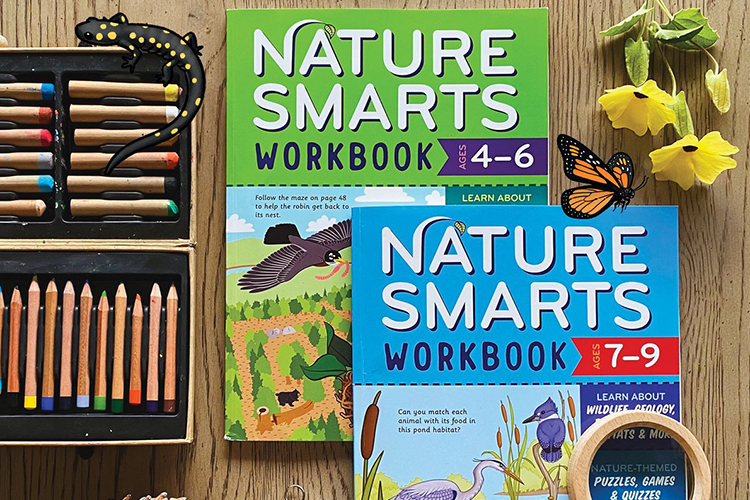

Nature Smart Workbooks

STEM-based workbooks for children packed with interactive learning activities with an emphasis on observational skills and the investigation method.

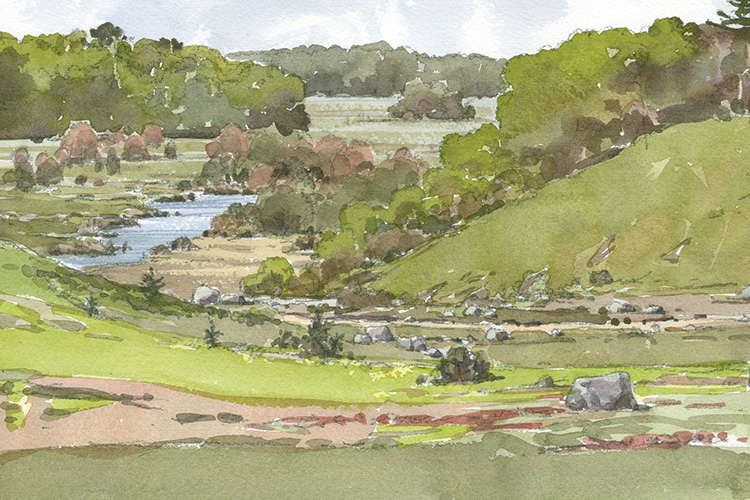

Finding Sanctuary

An Artist Explores the Nature of Mass Audubon.

Sanctuary magazine

A journal about natural history and the environment. The 200th—and final—issue was published in 2014.

Conservation Restriction Stewardship Manual

This helpful manual provides guidance for state-based land trusts and public agencies on managing conservation restrictions.