Find a Bird

Ruby-crowned Kinglet

Regulus calendula

Very local, trend not established

“Love or war is necessary to make the king show us his crown.” – Neltje Blanchan, Birds Every Child Should Know

Most of the time, the brilliant scarlet feathers that give Ruby-crowned Kinglets their name are concealed beneath a cover of dull greenish gray. When the male is alarmed by an intruder or wishes to attract a female, he will pull back the feathers that hide his splendid crown from view and display it for all to see. It’s not hard to catch a glimpse of a Ruby-crowned Kinglet during spring or fall migration, but finding a breeding individual in Massachusetts is much more difficult.

Historic Status

Massachusetts has long known the Ruby-crowned Kinglet, or the Ruby-crowned Wren as it was formerly called, as a definite migrant, the rarest of winter lingerers, and a breeder of more northern lands. “They can but rarely be detected here in winter,” wrote Henry Davis Minot, “since they commonly spend that season in the indefinite ‘South.’” (Minot 1877) Their nesting habitats remained mysterious well into the nineteenth century, as Minot observed. “It is astonishing,” he wrote, “under existing circumstances that neither nest nor egg of the Ruby-crowned ‘Wrens’ has been discovered, or at least described. It is probable, and on their account it is to be hoped, that they may long continue to rear their young in happiness and peace, undisturbed by naturalists, in the immense forests of the north,” (Minot 1877). On three July occasions between 1915 and 1932, adults with fledglings were found in Savoy, begging the question of whether historical breeding might have been overlooked in deep forest locations (Bagg & Eliot 1937).

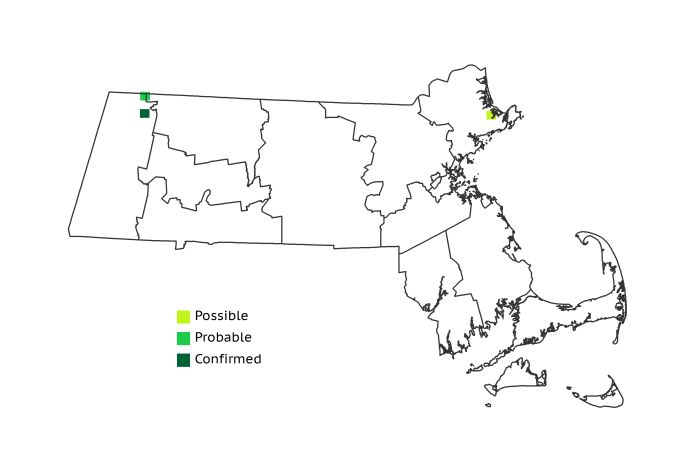

Atlas 1 Distribution

Given the limited number of well-documented historical breeding records of this species for the state, it stands to reason that the Commonwealth’s only Confirmed Ruby-crowned Kinglet breeding record in Atlas 1 came from the Berkshire Highlands near Savoy. Another record of Probable breeding near the Vermont border suggested additional breeding in Massachusetts. The Coastal Plains record, a lone singing male, never managed to attract a mate to his low-elevation coastal territory.

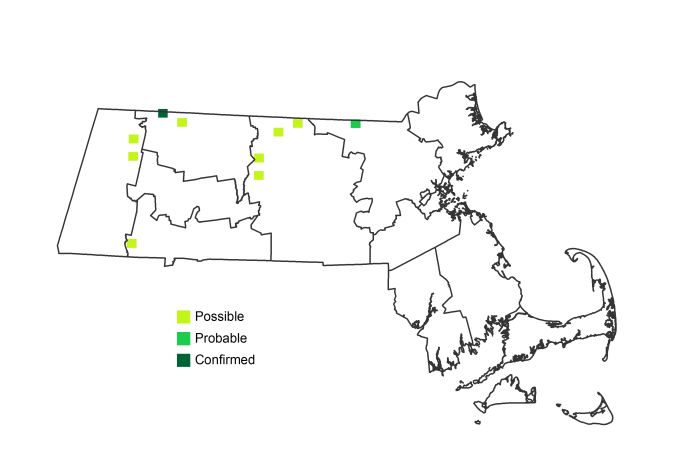

Atlas 2 Distribution and Change

One of the most rarely encountered breeding birds in the state, the Ruby-crowned Kinglet stayed steady at 1 breeding Confirmation, but appeared to be showing a slight increase in encounters during the breeding season. The Worcester Plateau, the Vermont Piedmont, and the Berkshire Highlands all showed some small new presence of potentially breeding kinglets.

Atlas 1 Map

Atlas 2 Map

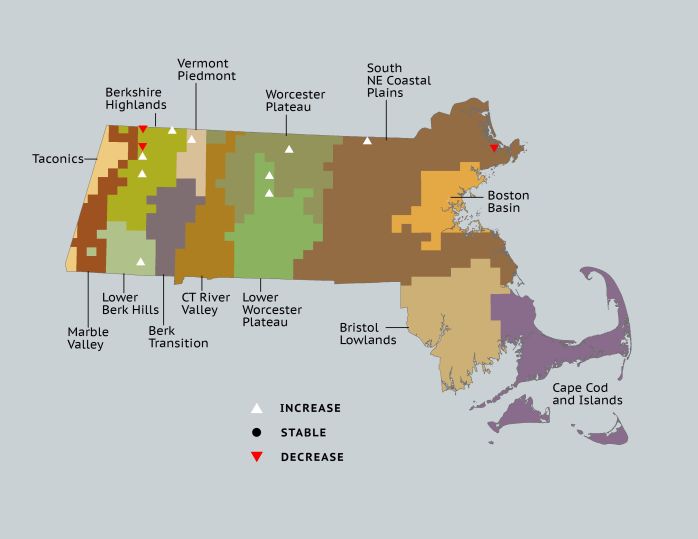

Atlas Change Map

Ecoregion Data

Atlas 1 | Atlas 2 | Change | ||||||

Ecoregion | # Blocks | % Blocks | % of Range | # Blocks | % Blocks | % of Range | Change in # Blocks | Change in % Blocks |

Taconic Mountains | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Marble Valleys/Housatonic Valley | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Berkshire Highlands | 2 | 3.6 | 66.7 | 3 | 5.5 | 30.0 | 1 | 1.9 |

Lower Berkshire Hills | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 3.2 | 10.0 | 1 | 3.7 |

Vermont Piedmont | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.9 | 10.0 | 1 | 8.3 |

Berkshire Transition | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Connecticut River Valley | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Worcester Plateau | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2 | 2.3 | 20.0 | 1 | 2.1 |

Lower Worcester Plateau | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2 | 2.5 | 20.0 | 2 | 3.7 |

S. New England Coastal Plains and Hills | 1 | 0.4 | 33.3 | 1 | 0.4 | 10.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Boston Basin | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Bristol and Narragansett Lowlands | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Cape Cod and Islands | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Statewide Total | 3 | 0.3 | 100.0 | 10 | 1.0 | 100.0 | 6 | 0.7 |

Notes

This phenomenon deserves a note of caution, however, since most of the gains in the species’ range only represent Possible breeding reports, meaning that a kinglet was only seen once in the block in suitable breeding habitat and within Safe Dates. No further indication of nesting was documented. In addition, most of these single sightings were within a few days of the beginning of the Safe Dates period, and the species was rarely recorded in multiple years in any single block. Taken together, these sightings suggest that some of these Possible locations may have been “prospecting” birds, and that the Atlas maps for this species may overestimate the occurrence of breeding for this species.