Find a Bird

Sedge Wren

Cistothorus platensis

Very local, trend not established

Conservation action urgent

Endangered Species

“Oh what can ail thee, knight-at-arms, / Alone and palely loitering? / The sedge has wither’d from the lake, / And no birds sing.” – John Keats, “La Belle Dame Sans Merci”

Few Sedge Wrens sing today from many of the places across the state where they were once well established. As their name suggests, Sedge Wrens prefer to nest in wet meadows of grass and sedge. Though they are small and elusive, they share the trait of a loud and distinctive voice with many other wren species. They are state listed as Endangered in Massachusetts today, but such was not always the case.

Historic Status

The Fresh-Water Marsh Wren (or later the Short-billed Marsh Wren, as the species was formerly called) moved eastward from the central portion of the United States as Europeans settled the continent, and in 1839 was described as a “summer visitor, not uncommon” (Peabody 1839). More telling, though, was the comment under the Salt-Water Marsh Wren (today’s Marsh Wren) in that same report suggesting that the species was “not so common as the preceding.” By the early twentieth century, the status had been reversed, with Edward Howe Forbush describing the Sedge Wren as “not as common as the other species,” (Forbush 1907). Loss of freshwater wetlands throughout the rest of the twentieth century robbed the Sedge Wren of its nesting habitat.

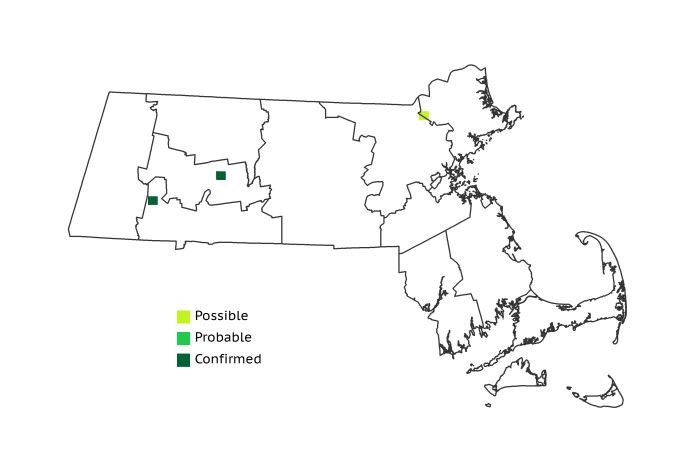

Atlas 1 Distribution

Though it may never have been a common breeding species in the Bay State, to all appearances Sedge Wrens were seemingly making their last stand against extirpation in Massachusetts during Atlas 1. A trio of lonely blocks scattered across the state were the only signs of breeding activity at that time. The Berkshire Transition Confirmation was in an old sedge-dominated Beaver pond in Blandford, whereas the Connecticut River Valley nest was found in Hadley near a hay field that had hosted Sedge Wrens prior to the Atlas 1 period. The single Possible block in the Coastal Plains may have represented a late wanderer or simply a lonely male, but even if it was a bona fide nesting location, Sedge Wrens clearly deserved their current status as an Endangered species in the Commonwealth.

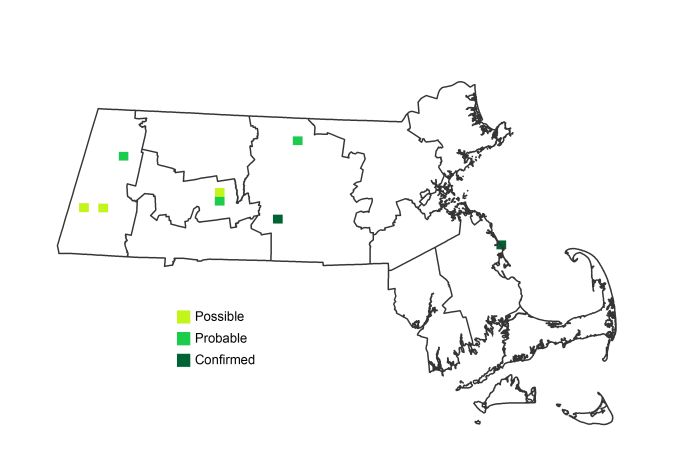

Atlas 2 Distribution and Change

Unfortunately, Sedge Wrens had not profited much from their protected status by Atlas 2, and the species remained one of the rarest of the state’s regularly occurring breeding birds. They were only found in 8 blocks during Atlas 2, an increase since Atlas 1, but still a precariously low distribution, with no persistence exhibited in any one block.

Atlas 1 Map

Atlas 2 Map

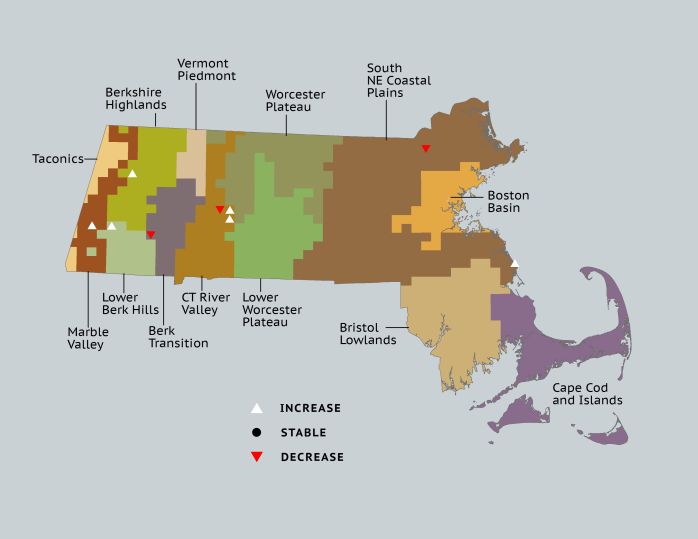

Atlas Change Map

Ecoregion Data

Atlas 1 | Atlas 2 | Change | ||||||

Ecoregion | # Blocks | % Blocks | % of Range | # Blocks | % Blocks | % of Range | Change in # Blocks | Change in % Blocks |

Taconic Mountains | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Marble Valleys/Housatonic Valley | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.6 | 12.5 | 1 | 2.6 |

Berkshire Highlands | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.8 | 12.5 | 1 | 1.9 |

Lower Berkshire Hills | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 3.2 | 12.5 | 1 | 3.7 |

Vermont Piedmont | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Berkshire Transition | 1 | 2.6 | 33.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -1 | -3.2 |

Connecticut River Valley | 1 | 1.8 | 33.3 | 2 | 3.1 | 25.0 | 1 | 2.1 |

Worcester Plateau | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.1 | 12.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

Lower Worcester Plateau | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.3 | 12.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

S. New England Coastal Plains and Hills | 1 | 0.4 | 33.3 | 1 | 0.4 | 12.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

Boston Basin | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Bristol and Narragansett Lowlands | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Cape Cod and Islands | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Statewide Total | 3 | 0.3 | 100.0 | 8 | 0.8 | 100.0 | 3 | 0.4 |

Notes

This apparent “gain” in blocks could easily be the result of increased effort to find state-listed species during Atlas 2, since the state did not even have an Endangered Species program during Atlas 1. Prospects of recovery for a species this far removed from its core population in the central US seem unlikely without “stepping stone” populations building in New York, where modest increases were reported in that state’s second Breeding Bird Atlas (McGowan & Corwin 2008).