Find a Butterfly

Mustard White

Pieris napi

Taxonomy & Nomenclature

This and the West Virginia White (Pieris virginiensis) belong to a perplexing spectrum of species, subspecies and/or forms sometimes referred to as the "napi complex". Until 1952, they were not distinguished as separate species. More recently some authorities have split napi into several full species. To complete the confusion, napi has distinctive seasonal forms which bear the same names as previously proposed species or subspecies. Many recent works refer to this species as a whole as "Veined White" and reserve" Mustard White" for the "subspecies" (Pieris napi oleracea) that occurs in the Northeast (including Massachusetts). We have followed Opler (1992) in recognizing "oleracea" as a summer form of napi, though this is questioned by other authorities.

This and the following species have been known to mate where their ranges overlap in New England (Chew, 1980), but not to produce viable offspring -- evidence of their distinctness.

Identification

Wingspan: 1 1/2 - 1 5/8". Lacks the black wing spots and forewing tips typical of the Cabbage White. The summer form, "oleracea", is clear white above and clear white below, sometimes tinged pale yellow on the forewing tip and hindwing below, but without heavy outlining of the veins of the hindwing below that is characteristic both of the spring form of napi and of the West Virginia White.

In Massachusetts the problem is to distinguish the spring form of Mustard White from that of West Virginia White which flies during the same period in similar habitat. The most useful characters are as follows:

1. Dark Vein Markings of Hindwing Below. This is by far the most useful character; the others are more variable and should be used as essentially corroborative. In West Virginia White these markings are paler, more blurry, and are brownish rather than gray-green; in Mustard White the veins of the hindwing below are outlined darkly and distinctly with gray-green scaling.

2. Shape of Forewing Tips. In general, comparatively rounded in West Virginia White; more pointed in Mustard White. But variable with at least some individuals of the summer form of napi having more rounded tips.

3. Wing Texture. West Virginia White has notably translucent wings; in Mustard White the wings are less translucent, but by no means "opaque", as is often stated.

4. Tint on Underwings. In West Virginia White suffusion of the darker scales makes the underside of the hindwings appear tawny in many individuals, contrasting with the forewing. Experience with both species makes this distinction clear, but contrasting "yellowish" hindwings is not a definitive character for Mustard White. Underwings are yellow in Mustard White, but color may fade and be inconspicuous.

5. Manner of Flight. Both species fly weakly compared to the Cabbage White. However, West Virginia White tends to be more skittish and erratic, often flying out of reach when alarmed. By comparison napi has been characterized as "docile" and "easily netted" (Howe, 1975), though Opler (1984) says the flight is more rapid than that of virginiensis, and some field observers are dubious of any such distinction.

6. Habitat. West Virginia White is less likely to be found away from forest habitat where its food plant occurs exclusively (see below). Napi feeds on a wider variety of mustard species, some of which occur in more open habitats, and is therefore somewhat less attached to wooded areas.

7. Season. While both species fly in April and May in Massachusetts, any "unspotted" white seen after mid-June should be Mustard White.

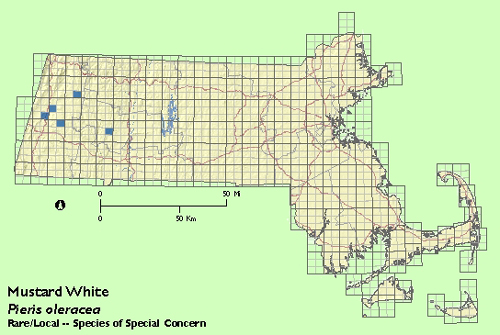

Distribution

Holarctic. In North America, napi ranges from above the Arctic Circle in Alaska south in the mountains to Southern California, Arizona, and New Mexico, east through Canada and the northern border states to Labrador and Newfoundland (isolated populations) and south to Massachusetts.

Status in Massachusetts

Scudder (1889) found Mustard White "swarming" in Harvard Yard, Cambridge in 1857 and remarked on its rapid decline shortly thereafter coincident with the introduction and spread of the Cabbage White. Since then it has been widely supposed that this species‘ changes in status were due to "competition" with the Eurasian invader. As usual, however, the facts are somewhat more complex. For example, Chew (1977) has demonstrated a likely relationship between the decline of the Mustard White and the introduction of the Eurasian mustard Common Winter Cress (Babarea vulgaris); while napi will lay eggs on this (now abundant) weed, the larvae cannot complete development on it. Chew further speculates that once the Cabbage White began to dominate in the use of weedy, open-habitat mustards, the Mustard White retreated to the forest habitat of its preferred food plant, Toothwort (Dentaria diphylla). It is also plausible that the many wasp parasites that have been imported to combat the agricultural destructiveness of Cabbage White have helped "drive" the Mustard White back to the woods.

Regardless of the explanation, it is clear that at present the Mustard White is rare and local in Massachusetts, where it occurs at higher elevations west of the Connecticut River Valley. Of the five atlas records, all but one are from Berkshire County. Maximum: 8, Pittsfield (Canoe Meadows Wildlife Sanctuary), (Berkshire County), 22 July 1986. It is unclear whether this species is continuing to decline as some suspect.

Flight Period in Massachusetts

Difficult to define with precision given the small number of records. This is among the earliest of non-hibernating butterflies on the wing in Massachusetts. There are apparently three flight periods: late April to mid-June; early July to early August; and late August to the third week in September (fide Miliotis, 1972). Extreme dates: 22 April 1986, Lenox (Berkshire Co.), T. Tyning.

Larval Food Plants

A variety of mustards (Cruciferae): Toothwort (Dentaria diphylla), Tower Mustard (Arabis glabra), Early Winter Cress (Barbarea verna)*, Rape (Brassica rapa)*, Black Mustard (Brassica nigra)*, Cuckooflower (Cardamine pratensis), Wild Peppergrass (Lepidium virginicum), Watercress (Nasturtium officinale)*, Wild Radish (Rhaphanus raphanistrum), Marsh Yellow Cress (Rorippa islandica). Chew (1977) has demonstrated that use of these species varies greatly with season and location and that certain species (especially Toothwort) are preferred when available. She has also shown that the species will lay eggs but cannot mature on two abundant alien weeds, Common Winter Cress (Barbarea vulgaris) and Field Pennycress (Thlaspi arvense), and this is also the case with the rapidly spreading alien, Garlic Mustard (Alliaria officinalis)*, which invades wooded areas.

Adult Food sources

Most frequently recorded on the flowers of the mustards the species uses as food plants, many of which bloom from earliest spring to late fall.

Habitat

Now mainly associated with rich deciduous woodlands where its preferred foodplant, Toothwort, thrives. However napi is less likely than its close relative, the West Virginia White, to be found inside the forest, preferring nearby edges and open areas including meadows and bogs. Sometime during the 1800‘s, as deforestation reached its peak in the Northeast, it apparently began to utilize open country and even weedlot mustards to such an extent that it grew abundant even in eastern cities (Scudder, 1889). Following the introduction of the Cabbage White and certain alien mustards, however, and as the region became reforested, it apparently retreated to its ancestral habitat (See also under Status, above.) Members of the early spring brood tend to keep to the forest more than those flying later.

Life Cycle

EGG: White to greenish yellow, spindle-shaped OVIPOSITION: Eggs are laid singly on the underside of the food plant leaves. LARVA: Green with black dots; pale-striped on top and sides with a short pile of fine hairs. CHRYSALIS: Light brown to blue gray or green with black dots, yellow stripes along top and sides and a prominent head "horn". PUPATION: Attaches head upward to a vertical surface by means of a silk girdle and a holdfast (cremaster) at the tip of the abdomen. OVERWINTERING STAGE: Chrysalis.

Account Author

Chris Leahy

Additional Information

Read more on this species at the North American Butterfly Association.